The Church as the Body of Christ

The word translated “church” in English is the Greek word ekklesia. It means “gathering” or “assembly,” regardless of the purpose of the gathering. In Acts 19:41, it is used to describe an ad hoc gathering of angry Gentiles, assembling to protest the work of St. Paul, whose labors were cutting into their profits as makers of idols. It is the translation of the Hebrew qahal. The word qahal is used in Judges 20:1 to denote Israel assembled for military battle, and in Deuteronomy 9:10, where it describes Israel gathered at the foot of Mount Sinai to meet God. In the New Testament the word most often refers to the gathering or assembling together of Christian believers into a group for the purpose of Eucharistic worship on Sunday.

Christ had promised that He would manifest Himself and be spiritually present in their midst whenever they assembled, even if the eucharistic gathering of all the Christians in a town was small, consisting of only two or three (Matt 18:20). In their gatherings, the Christians were therefore not merely reflecting upon an historical Christ who was now absent but were invoking a living Christ who had promised that He would be with them until the end of the age (Matt 28:20). When the Christians assembled as an ekklesia, Jesus Christ was in their midst. It is this weekly miracle that is celebrated in the standard Orthodox liturgical greeting, “Christ is in our midst!” (The reply is significant: “He is and will be!”—i.e., He is present now and will be even more so after the Second Coming.)

It is because of this reality of Christ’s promised presence among his people that the ekklesia is called “the Body of Christ.” Just as a person lives, works, speaks, and manifests himself through his body, so Christ lives, works, speaks, and manifests Himself in and through the assembly, the Church. Although there are many images of the Church in the New Testament (the Church as branches of a vine, the Church as God’s household, the Church as bride, the Church as God’s city),1 the image of the Church as the Body of Christ is the most significant one. From this reality, three things follow.

First, when the Church gathers and finds Christ in their midst, He is present to transform and to heal. That is, Christ works today through his sacramental mysteries. In baptism, He grants the penitent forgiveness of sins, new birth, and sonship. In the Eucharist, He feeds his people with his Body and Blood and bestows upon them “purification of soul, the communion of the Holy Spirit, and the fulfillment of the Kingdom of Heaven.”2 In ordination, He fills the elected candidate with his Holy Spirit to enable him to fulfill his tasks. In unction, He grants healing and forgiveness. The visible celebrant is the one performing the sacraments of baptism, eucharist, ordination, or unction, but the real celebrant is Christ, who works invisibly through His Church. As St. Leo the Great once wrote, “Our Redeemer’s visible presence has passed into the sacraments.”3 That is why in the early Church all these other sacramental rites were usually performed within the context of the Eucharist, when the people gathered to find Christ among them.

Second, when the Church proclaims its message, it speaks with the authority of Christ Himself, since it is his Body. That is why St. Paul described the Church as “pillar and bulwark of the truth” (1 Tim 3:15) and wrote that it was through the Church that Christ’s manifold wisdom was revealed (Eph 3:10). The Church’s message is the message of the living Christ Himself. This is what theologians mean when they declare that the Church is infallible. It does not mean that everything that every bishop or priest says is true. But it means that when the Church speaks as the Church, expressing its mind and its settled teaching, the message may be received as entirely trustworthy, reliable, and true.

was revealed (Eph 3:10). The Church’s message is the message of the living Christ Himself. This is what theologians mean when they declare that the Church is infallible. It does not mean that everything that every bishop or priest says is true. But it means that when the Church speaks as the Church, expressing its mind and its settled teaching, the message may be received as entirely trustworthy, reliable, and true.

That is because, thirdly, the Church will never be forsaken or abandoned by Christ, but He will always be present to guide them. We see this in his promise that his Spirit would lead them into all truth and that the gates of Hades would never prevail against them (John 16:13; Matt 16:18). The question may be asked: how can the authentic voice of the Church be discerned? The answer: through the ecumenically received work of the councils, the writings of the Fathers, the liturgy, and the spiritual practices.

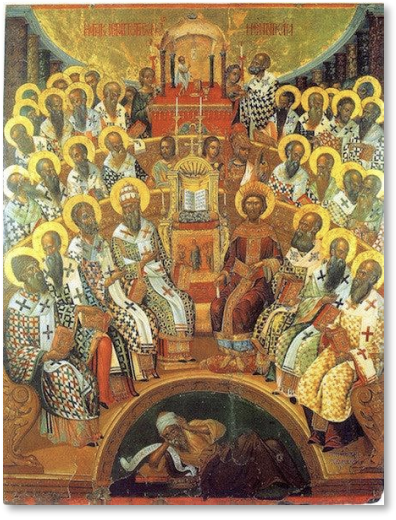

An even cursory examination of Church history reveals that this guidance takes time and involves his people debating, arguing, and struggling to reach a final consensus. The results of this consensus can be found in the works of the councils that were finally accepted by the Church throughout the ecumene, the “inhabited world”, as containing the truth (the so-called “ecumenical councils”). Sometimes, this process of receiving the findings of a council took decades (for example, in the case of the Council of Nicaea in 325). But eventually, when the Church did reach a settled consensus of the majority, this was accepted as the result of the Spirit’s guidance.

The bishops throughout the history of the Church have held many councils and produced many definitions. Some were true (e.g., Nicaea in 325, which declared that Christ was of the same divine essence as the Father), and some were not (e.g., Hieria in 754 which condemned icons as idolatrous). After councils were held and did their work, it took time for the faithful throughout the world to decide whether to accept the work of the council as true or not.

It was this final acceptance and reception of a council which gave it status as an “ecumenical council”— a council accepted as true by the Church at large throughout the world. The work of these councils, being finally accepted by the faithful worldwide, held the true teaching and authentic voice of the Church.

A large part of this historical witness was the contribution of the Fathers. The Fathers were an immensely varied lot, spanning great distances and many centuries, and writing in different languages. They differed from each other and did not always agree with each other (some of them had famously and scandalously public conflicts, such as Jerome and Augustine). But they agreed upon many things, and it was this underlying agreement upon the core teachings of the Faith (the so-called “consensus patrum”) that constitutes the patristic message.

Their message was further confirmed by the eventual universal acceptance of some men as reliable expressers of the apostolic message. To be a true Father, one needed to be accepted universally in the same way as the true church councils were universally accepted. That is why, for example, Cyril of Alexandria was accepted as a true Church Father, while Nestorius of Constantinople was not. Both proclaimed their messages, but the Church at large eventually came to see that Cyril’s message was consistent with the truth, while that of Nestorius was not.

We also hear the Church’s true voice in its liturgical worship, (compare the formula lex orandi, lex credendi, “the law of prayer is the law of belief”). That is, we can tell what the Church believes by how it worships. For example, the Church’s belief in the importance of Mary as the Mother of God may be gauged by the many prayers offered to honour her and ask for her intercession; the Church’s belief in the Real Presence of Christ and the sacrificial nature of the Eucharist may be seen in the words of the anaphora and other prayers of the Divine Liturgy.

The authentic voice of the Church may also be discerned from its spiritual practices such as the content of its icons and its hymns. The Church’s belief in the reality and eternity of damnation, for example, may be learned from its icons of the Last Judgment, and from the many hymns and prayers describing the punishment of the lost as eternal.

Thus, the work of the ecumenical councils and of the Fathers, the words used in the Church’s liturgical worship, and the entirety of its spiritual culture together form a single whole proclaiming the teaching of the Church in a pluriform and variegated way. Ultimately the work of hearing the true voice of the Church and of authenticating its message falls to the faithful, the true guardians of the Faith. The bishops might proclaim a message, but it is up to the ordinary members to either accept their work or refuse it.

Christ guides His Church through the entirety of its members, not through select chosen individuals, such as bishops of given cities, be they from Rome or Constantinople