The Martyric Church

If the first Christians imagined that the fulfillment of God’s promises to bless his people and glorify them in the world meant that they would experience no opposition, they were soon taught otherwise. The Lord Himself warned them of this, saying, “If they persecuted Me, they will also persecute you” (John 15:20), and the persecution which engulfed the infant Church after the day of Pentecost abundantly fulfilled his words (Acts 4:5–31, 5:17–39, 8:3). As first the persecution came from the Jews who did not believe that Jesus was the Messiah, the Romans functioned as rescuers of the Christians. But soon enough, the Romans themselves also turned against the Christians, and the Church found itself under threat from all sides.

The first fierce persecution from the Romans came at the hands of the emperor Nero, after the great fire in Rome in the sixth decade of the first century. The Christians were commonly thought by Roman society at large to be polluted wretches, and thus were an obvious target, as Nero arrested and killed Christians in the area around Rome—a persecution which claimed the lives of Peter and Paul.

Soon enough, however, the scope of the persecution widened, and Christians throughout the entire empire were in danger. They were universally hated, and subject to legislation outlawing their assemblies and threatening their very existence. The persecution heated up so that by the time of the emperor Diocletian at the end of the first century, Christians began to live under threat of arrest, exile, or worse.

They were universally hated, and subject to legislation outlawing their assemblies and threatening their very existence. The persecution heated up so that by the time of the emperor Diocletian at the end of the first century, Christians began to live under threat of arrest, exile, or worse.

The reasons for the “halo of hatred around the Church of God”1 were many and varied. The whole of society, education, and culture in the Roman world were built upon the foundation of the worship of the pagan gods—a worship which affected everything, including such everyday things such as the meat sold in the market (see 1 Cor 8-10). Christians would have nothing to do with such idolatry and refused to eat the food set before them, if they knew it had been offered to idols (1 Cor 10:28–29). This meant that their daily existence was dramatically impacted by their faith, and they soon had a reputation as a group that hated their neighbours and the society around them.

Furthermore, the comparative secrecy of their assemblies helped perpetuate misunderstandings and further contribute to their bad reputation. Talk about “eating the Body and drinking the Blood” (i.e., receiving the Eucharist) and about Jesus being the pais theou (the child/servant of God2) led to the misunderstanding that the Church was engaging in cannibalizing infants. Talk about the “brothers and sisters” exchanging “the kiss” (the Kiss of Peace) led to accusations that the Church engaged in incest. No wonder the Christians in those days were hated.

The persecution of the Church was sporadic but sustained. The laws decreed that Christians were not allowed to exist, but the enforcement of the laws depended upon circumstances, the mood of the mob, and the clemency of the local rulers. But whether Christians were arrested, tortured, and killed or not, the threat of such things always hung over their heads. The Church of the first three hundred years was a martyric Church, a Church in which baptism and attendance at the Eucharist could lead to exile, torture, or death.

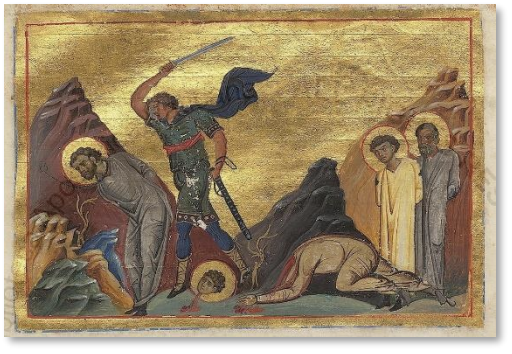

Many in fact did suffer the ultimate penalty for their faith, and the Church from the start honored them as the truest of disciples, the athletes, and heroes of Christ. The confessors (who continued to confess their faith even under torture) and the martyrs (who died for Christ) were held in the highest honor. The stories of the martyrs were recited and shared, and the anniversaries of their martyrdoms (called their “birthdays”, since they were born above in heaven on that day) were commemorated every year, if possible, by serving the Eucharist above their tombs. After Pascha, the feasts of the martyrs were the earliest commemorations on the Church’s developing calendar.

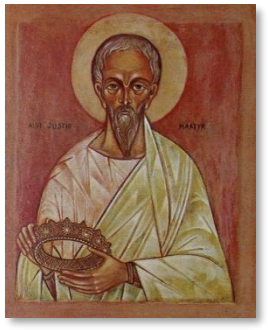

As a response to such persecutions, a number of Christians undertook the task of writing to defend the Church, denying the charges that Christians were doing anything wrong or criminal, and explaining how the worship of the Christian God was reasonable and good, and further explaining why the Christians refused to worship the traditional gods of the pagans. These men were known as “the Apologists,” since they offered an apologia or defense of the faith. Justin, writing and teaching in Rome, offered two written defenses of Christianity, as well as an explanation (in his Dialogue with Trypho) of why Christianity was preferable to Judaism, the other major non-pagan form of monotheism in the Roman Empire that was seeking converts. Justin was martyred for his faith in 165 A.D. Another Christian who aggressively defended the faith was Tertullian, writing from North Africa somewhat later.

and further explaining why the Christians refused to worship the traditional gods of the pagans. These men were known as “the Apologists,” since they offered an apologia or defense of the faith. Justin, writing and teaching in Rome, offered two written defenses of Christianity, as well as an explanation (in his Dialogue with Trypho) of why Christianity was preferable to Judaism, the other major non-pagan form of monotheism in the Roman Empire that was seeking converts. Justin was martyred for his faith in 165 A.D. Another Christian who aggressively defended the faith was Tertullian, writing from North Africa somewhat later.

As well as threats from outside the Church, the faith was threatened by error from within. This included threats from some Christians whose explanation of Christianity distorted the Scriptures and incorporated the Church’s proclamation of Jesus into alien systems of thought. Those teaching these distortions were many and varied, and usually are known under the general term “Gnostics”, those with special and secret gnosis, or knowledge. What almost all the Gnostic systems had in common was a rejection of the goodness of the created world and a rejection of the creator God of the Old Testament as the one true God.

Christians like Irenaeus, teaching in Lyons, outlined the various competing Gnostic systems and argued against them in his massive work Against Heresies. Irenaeus focused upon the apostolic tradition of teaching that could be found in all the major episcopal centers (such as Rome) as the standard, condensing that teaching into a canon or rule of faith. He died in the year 202.

The first three centuries were times of immense conflict, as the Church battled enemies without and within. There were also times of growth, as the number of Christians increased dramatically despite the persecutions, so that Tertullian observed that the blood of the martyred Christians functioned like seed for growth.3 The growth was most dramatic in the cities. The Christians were everywhere and were impossible to ignore. At the beginning of the fourth century, a determined attempt was made by the emperor to eliminate them from the life of the empire in a long persecution stretching over a decade. It was the climax and culmination of a long struggle.