Components of the Written Gospels Genealogies and Beyond

If the Gospels were merely biographies, all four of them would have to include genealogies, because this is an essential component of the ancient genre. Matthew and Luke do include them, but in such a way as to surprise the reader, and also to intimate the Gospel itself. Non-Orthodox who visit an Orthodox church on the Sunday before Christmas are frequently astonished to see us standing for the long reading of Matthew’s genealogy. Many consider the “begats” of both the Old and New Testaments to be mere padding, a context for the real story. But for us, the concrete nature of Jesus’ humanity is central—He truly was born of Mary and had a human history!

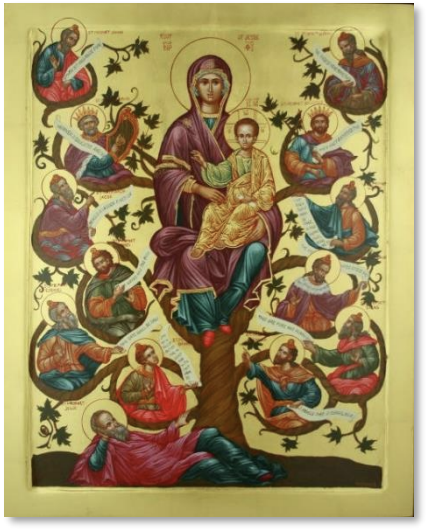

But there is more to it than that. The genealogy of Matthew contains four little surprises that prefigure the surprise of the Incarnation itself. Amidst the ancient fathers listed, as in a normal genealogy, there are four women: Tamar, Ruth, Rahab, and Bathsheba. And what women they are! All four of them were questionable, by standards of Jewish piety—three of them were not even Jews by birth, one of them was a harlot, and two of them were involved (though against their will) in illicit sexual conduct. Yet there they are, in the middle of Jesus’ pedigree. Rahab the harlot becomes so important in early Christian preaching that she is mentioned not only here, but also in the epistle to the Hebrews and in the letter of James, as an example of Gentile faith. The implicit lesson signaled by the presence of these four is that Jesus came to fulfill the needs of the wretched and not only the pious, of the Gentiles and not only the Jews, of women as well as men.

A similar theological take-away comes out of Luke’s genealogy, which traces backwards from Joseph and Mary—the son of this one, the son of that one—to Adam, “the Son of God” (Luke 3:23–38) Luke’s point is that Jesus, though nurtured in Joseph’s family, though born of Mary, and though the beneficiary of all the DNA passed on by his ancestors through her, is also “the Son of God”—and in a more direct, personal, and profound way than Adam, the first-created. For He is the Only-begotten Son, and not merely a creature, though He is also fully human.

The fourth Gospel, in recognition of this, goes beyond human genealogy to a time before the beginning, where the evangelist pictures the Word in communion literally “towards the Father,” (pros ton theon, John 1:1), and with the Spirit.1 He is the Son that enlightens every human being who comes into the world (John 1:9). And yet, says John, He became man, and dwelt among us, coming to his own “who did not receive Him” (John 1:11). The Son is “in the bosom” of the Father, and “exegetes”2 Who the Father is to us (John 1:18).

Footnotes

-

The image is that of the Son with the Holy Spirit leaning in toward the Father to catch his every word and know His every desire. This “leaning in” is most beautifully illustrated in Rublev’s famous icon (opens in a new tab) of the Holy Trinity, in which angels, who represent the figures of the Son and Holy Spirit, in full communion with the Father, incline their heads toward him. ↩

-

In this case, the Son reveals who the Father is. ↩