Jesus

In the same way that popular thought has sought to tame, sanitize, diminish, and render the living God safe and harmless, the Jesus of history has been similarly dealt with. Just as the everlasting Father and Judge has become in many people’s minds an indulgent grandfather and a kind but ineffectual senior citizen, so Jesus, the Son of Man, has been transformed in the popular mind as an affirming, inclusive, non-judgmental teacher of love, a flowered guru, one in a long line of human teachers. The Jesus revealed in the New Testament and described in the hymns of the church, however, is nothing like this modern substitute. The Jesus of the hymn “Only Begotten Son”, and the Jesus of the scriptures and of the councils is not a mere human teacher but the divine Son, who has unique and specific activities in the world.

The New Testament reveals his compassion clearly enough. Jesus is the One who taught his disciples to pray for their enemies and to forgive. He refused to call down fire upon the Samaritans when, in defiance of all the sacred norms of Middle Eastern hospitality, they refused to receive him as He traveled (Luke 9:53–56). In gentleness, He welcomed children and infants, taking them in his arms and blessing them when his disciples would have sent them away (Luke 18:15–16). He prayed that God would forgive those who were crucifying him (Luke 23:34).

There is more than enough Gospel material to justify the common picture of “gentle Jesus, meek and mild.” But this picture is only half the Gospel picture. If Jesus was meek and mild, He also walked the earth with a sovereign stride, utterly aware of his divine authority and dignity as the Son of God. He knew that He possessed authority to forgive sins and He walked on the sea as easily as other men walked on the road. More than that, He knew that He had the authority to pass along his miracle-working authority to others, such as the apostles, and He sent them out with instructions to cleanse lepers, cast out demons, and raise the dead as easily as anyone else would send out a friend with instructions to pick up their mail while they were out (Matt 10:8). He took it for granted that it was his word and decision alone that would one day determine the eternal fate of every living person (Matt 7:22–23, 25:31–46). In the words of G. K. Chesterton, Jesus was “a being who often acted like an angry god—and always like a god.”1

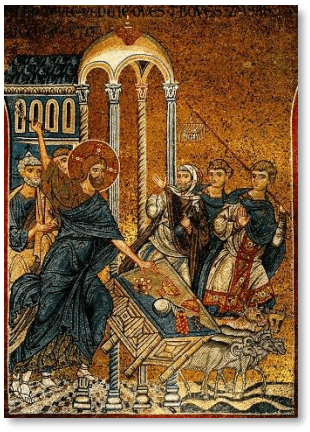

Christ’s anger, reminiscent of the anger of Yahweh in the Hebrew scriptures, was at least as obvious as his compassion. He cast the money changers out of the Temple, driving out their animals with a whip of cords (Mark 11:15; John 2:15). He denounced the Pharisees with a tremendous tonguelashing, calling them a brood of vipers, hypocrites, blind guides, and fools, and when Law-experts heard this and protested that by saying this He was insulting them too, He did not qualify or relent, but turned on them also, saying, “Woe to you lawyers, as well!” (Matt 12:34; 23:15–16; Luke 11:45). He told those who were his foes that they were children of the devil, and by his imprecation sank unbelieving Chorazin, Bethsaida, and Capernaum into the depths of Hades (John 8:44; Matt 11:21– 23)—an angry God indeed!

This double Gospel picture is confirmed by the vision that St. John had in later decades when Christ appeared to him in glory with messages for seven churches in Asia Minor. For some churches, Christ had only words of encouragement and compassion. For others, He had words of stunning rebuke. He told the Ephesian Christians that they must repent, or He would remove their church entirely; to the Smyrnaean Christians, He said that if they did not repent, He would make war against them with the sword of his mouth (i.e., would utter judgments destroying them). To a false prophetess in Thyatira, He said that if she did not repent, He would cast her upon a bed of sickness and kill her children (i.e., her followers) with pestilence. To the lukewarm Christians of Laodicea, He said that unless they repented, He would vomit them out of his mouth (Rev 2:5, 16, 22, 23, 3:16).

The Gospel picture of Jesus includes therefore promises of unimaginable glory and reward as well as threats of terrifying retribution. The Jesus of the Law walked the land with sovereign authority, healing all who came to him—opening blind eyes, raising the dead—and demanding complete submission, saying that no one was worthy of him unless they preferred him even to their families and their own lives (Luke 14:26).

Although Jesus answered to the title “Son of David,” which was a messianic title (Matt 22:42, 15:22; Mark 10:47), his preferred title was “Son of Man,” doubtless because the title “Son of David” or “Christ/Messiah” contained too many military and political connotations in the popular mind.

The title “Son of Man” originally simply meant “a human being,” which is its meaning in Psalm 8:4 and Ezekiel 2:1. It was used in Daniel 7:13–14 to refer to the people of Israel as the image of a human being to contrast them with the brutal animal-like kingdoms that oppressed them (such as Babylon and its successors, which were compared to a lion, a bear, and a leopard). The human being/son of man was brought near to God and received from him tremendous authority. This was an image of Israel being glorified and saved from foreign domination, when “the dominion and the greatness of all the kingdoms under the whole heaven will be given to the people, the saints of the Most High” (Dan 7:27).

The image very quickly came to be an image not of the saints of the Most High, but of the Messiah who would bring them dominion. (The Book of Enoch, for example, uses the title “Son of Man” as a title for the Messiah.) Jesus adopted the title for Himself, for it spoke of his authority and of his glorious destiny as the Messiah at the Father’s right hand but was free of the military associations surrounding the title “Messiah”.

The New Testament picture of Jesus is therefore one of divine authority. Jesus claimed this divine authority as his own, and in fact asserted his full divinity, saying that He was “one with the Father” and that He was the eternal “I am” who revealed Himself to Moses at the burning bush (John 10:30, 8:58; Ex 3:14). The Church would, in the coming centuries, confess both his full humanity and his full divinity, combined in one Person, the divinity and humanity existing together “unconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably.”2

Thus, through his incarnation, crucifixion, and resurrection, Jesus, the Son of Man, brought salvation. Those uniting themselves to him through faith and in baptism became part of his Body the Church. In the Church, the gathering of his disciples, the new aeon, the age to come, is manifested and actualized. In his presence among his assembled disciples, the powers of the coming age are now at work. his disciples are given a new and eternal life, experiencing the power of the age until now in this world. As such, they are different from those not yet united to Christ and are called by Christ to reveal him by living differently than other men.

Read more: Jesus Christ (opens in a new tab), Son of God (opens in a new tab),