What is a Gospel?

When we think about “the Gospel” in the Divine Liturgy, we picture it as an event when God’s word is proclaimed from one of the four evangelists so that we meet Christ. Just before we are to hear the Gospel, the priest proclaims to us, “The Lord is with you,” and we respond, with joy, “and with your spirit!” Our perspective differs from some Protestants, who frequently think of the gospel reading as instruction, and as raw material for the brain and for the preacher’s exposition. And from other Protestants, whose gospel readers instruct the congregation to “listen for the word of the LORD,” as though the position of the listener were to discern and judge, searching for something meaningful in a conglomerate of human words. Instead, we Orthodox anticipate the Word heard as something to be joyfully and obediently received, and as accompanied by the living presence of the incarnate Word, God the Son.

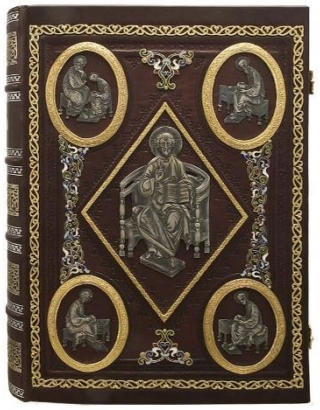

Worship, then, draws us into God’s presence, and the Gospel-book is celebrated as the central focus of the “Little Entrance”—a dramatic encounter with the living God in the Liturgy. (Some have wrongly thought that the two “entrances” refer to the emergence of the priest and others from the altar, into the congregation; instead, they are called “entrances” because we enter into God’s presence.) Thus, the priest prays on our behalf: “O Master, Lord our God, Who hast appointed in heaven ranks and hosts of Angels and Archangels for the ministry of Thy glory: Cause that with our entrance may enter also the holy Angels with us serving Thee, and with us glorifying Thy goodness.” God takes the initiative, speaking to us, and inviting us to approach him more deeply, by means of the Gospel. Even the fact that the Gospel is chanted reminds us of this solemn meeting: this is God’s own “everlasting” or “eternal gospel” (Rev 14:6) and does not require a dramatic performance by an emotive reader, or the critical discernment of the listener, to make its mark.

Because of all this, the reading of the Gospel is an audience with God, for which we stand, as we honor the presence of Christ in our midst. He is with us, speaking divine words. But the Gospel is also written in human words for human ears. Thus, when we hear “the gospel,” or “good news” (Greek, evangelion) proclaimed, it is helpful to contemplate the Gospels themselves. What is a gospel, what is its genre, and how does it do its work on the faithful? Which first-century conventions of writing did the four evangelists follow, and which did they modify? What expectations should we have of it, as we begin to read and to listen?

Already we are the recipients of significant steps of interpretation that have taken place in the Church long before we hear the words proclaimed. After all, passages have been selected (both as part of the canon of the Bible, and as an item in our lectionaries), and they have been translated from Greek (with the occasional word of Aramaic) into English. But selection and translation only go part-way in making the words plain to us. The homily will also help us to understand, and to respond to the words, as in the days of Nehemiah and Ezra, when the Jewish people returned from their exile and heard God’s Word afresh: “So [Ezra and his helpers] read distinctly from the book, in the Law of God; and they gave the sense and helped [the people] to understand the reading” (Neh 8:8).