Narrative of Jesus’ Death and Resurrection

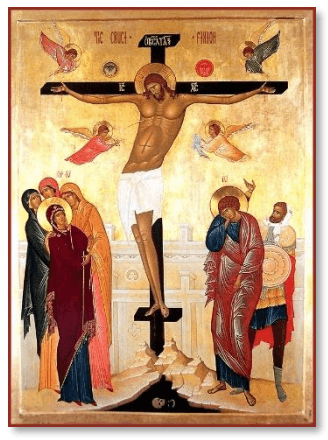

For many Christians, this is the very center of the Gospel: they cling to gospel songs like “The Old Rugged Cross,” and quote St. Paul’s words about our faith being in vain if Christ is not risen (1 Cor 15:17). For Orthodox, the utter significance of Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection is seen in our weekly Liturgies, in the ubiquitous cross, in our Holy Week services. But these mighty acts of God find their dramatic and effective place within the larger narrative of salvation history from Adam and Eve through the call of Israel and the Gentiles, within the specific narrative about Jesus from His Incarnation to Ascension (and promised return), and within the cosmic mystery of the Triune God. The way in which each evangelist underscores these larger contexts is something that can be seen in the narratives of Gethsemane, Calvary, and the empty tomb. As we might expect, John’s Gospel intimates the larger human context with deft strokes: “Behold the Man!” (John 19:5) takes us back to Adam, as does Jesus’ breathing of the Spirit upon the apostles (John 20:22). In the crucifixion of Jesus, we see the true Human Being, dying the only good death, obedient to the Father, humbly giving all for his human brothers and sisters. In His Resurrection comes the power of new life, the first sign of a new creation. All the Gospel accounts of the crucifixion are connected with the history of Israel, for they tell their narratives with an eye to Psalm 21 (22): “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me;” “they wag their heads;” “Let God deliver him;” “for my clothing they cast lots;” “He has done it [i.e., “It is finished”])!” As Fr. Patrick Reardon explains, “Of all the psalms, Psalm 21… is par excellence the canticle of the Lord’s sufferings and death.”1

“He has done it [i.e., “It is finished”])!” As Fr. Patrick Reardon explains, “Of all the psalms, Psalm 21… is par excellence the canticle of the Lord’s sufferings and death.”1

Oddly enough, it is Mark’s Gospel, which is usually more reserved about Jesus’ divinity than the others, that subtly (and ironically) hints at the universal implications of the crucifixion, when an outsider (a centurion) exclaims, “Surely this was the Son of God!” (Mark 15:39). Matthew’s Gospel, in its peculiar telling of the crucifixion and resurrection also connects us with the unseen actions of Jesus, and the harrowing of hell:

And behold, the curtain of the temple was torn in two, from top to bottom; and the earth shook, and the rocks were split; the tombs also were opened, and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised, and coming out of the tombs after his resurrection they went into the holy city and appeared to many. When the centurion and those who were with him, keeping watch over Jesus, saw the earthquake and what took place, they were filled with awe, and said, “Truly this was the Son of God!” (Matt 27:51–54)

In this astonishing narrative, the Evangelist knits together the crucifixion and resurrection, showing how these together form one mighty act of God, and how death is swallowed up in life. His approach prefigures our own Divine Liturgy, which does not isolate a particular point in salvation history but relates the entire arc of the incarnate God’s action on our behalf. Matthew intimates by how he tells the story that the prophet Daniel’s promise of resurrection (Dan 12:1–3) is fulfilled in what Jesus has done. This is named purposefully in Luke’s resurrection narratives, when Jesus twice says that the Law, Prophets, and Writings looked forward to what would happen for our good (Luke 24:26, 24:46–7).

Footnotes

-

Fr. Patrick Reardon, Christ in the Psalms (Chesterton, IN: Ancient Faith, 2011), 41. ↩