Becoming a Priest

Intercession and Worship

As every priest is called to restore and preserve the bond between the Creator and creation, so every Christian assumes this vocation by participating in the priestly intercession of Jesus Christ, our true high priest. This is the second aspect of the “royal priesthood” (1 Pet 2:9) that the faithful enter into by means of their baptism and anointing with holy chrism. The first way we accomplish this is by continual praise and worship of God. It is not as though God needs our worship, as he is beyond all necessity. For one who loves God, it should be a natural outpouring of gratitude for his gifts of life and love. Even the universe hymns the glory of God: the psalmist writes, “The heavens declare the glory of God; and the firmament shows his handiwork” (Psalm 19:1); and in the prayers for blessing holy water we proclaim, “The sun sings to you, the moon glorifies you.” Likewise, the Anaphora of the Divine Liturgy reminds us that all the angelic hosts forever surround the throne of God chanting of his glory.1 These angelic choirs were of old joined by the human voices of the Levites, who assisted the priests in the liturgy of the tabernacle and Temple. And now, in the age of the new covenant, Christians mystically unite their song of praise to that of all creation, both visible and invisible.

Thanksgiving

Not only does a priest bless the Name of God by sending up glory, he also calls down God’s blessing upon creation. This is truly possible now that Christ has poured out sanctification upon the entire cosmos, hence restoring the goodness previously corrupted by sin and demonic powers. “For every creature of God is good, and nothing is to be refused if it is received with thanksgiving; for it is sanctified by the word of God and prayer” (1 Tim 4:4–5). In a general sense, every member of the Church can and should “in everything give thanks” (1 Thess 5:18); but more specifically, we are called to receive the world gifted to us and offer it up to God in thanksgiving so that he may bless and sanctify it, and so that we may in turn employ it for its right purpose—the food we eat, the tools we use, even the currency we spend. Through the union of all the faithful as Church, the Body of Christ, all of creation is restored and brought back into the dominion of God.

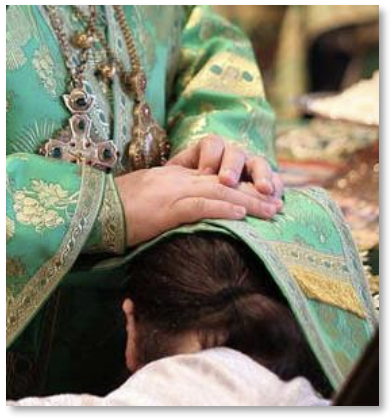

Laying on of Hands

The most specific way that we see the priesthood enacted in the Church is through the sacrament of “laying on of hands” (cheirotonia) or ordination. As in the days of the Aaronic priesthood, only a small number of qualified men are called to serve in the Temple and offer the bloodless sacrifice “on behalf of all and for all.”2 The biblical symbolism of male and female complementarity finds it fulfillment here, as the priest represents Adam who was appointed to serve sacrificially in God’s paradisiacal temple; and Eve (Zōē in Greek, the one who brings “life”) assists through constant prayerful intercession. Although male and female, in this context, fulfill different tasks, their spiritual labor comes together in their service to God. As Jesus Christ is our high priest (who, though a representative of all human beings, also assumed the physical, biological reality of a male), so his Mother the Theotokos is our prayerful intercessor (representing the complimentary female role of supporting the priestly vocation by prayer). These roles, illustrating a spiritual hierarchy of masculine and feminine are likewise imaged in marriage (see Eph 5:22–33, which is read at all Orthodox weddings). This spiritual hierarchy is also reflected in the local parish presided over by the presbyter when he is assisted by his wife, the presbytera.3 Such complementarity is not a denigration of one sex or the other, but both man and woman are equally beloved by God and redeemed in his Son.

and Eve (Zōē in Greek, the one who brings “life”) assists through constant prayerful intercession. Although male and female, in this context, fulfill different tasks, their spiritual labor comes together in their service to God. As Jesus Christ is our high priest (who, though a representative of all human beings, also assumed the physical, biological reality of a male), so his Mother the Theotokos is our prayerful intercessor (representing the complimentary female role of supporting the priestly vocation by prayer). These roles, illustrating a spiritual hierarchy of masculine and feminine are likewise imaged in marriage (see Eph 5:22–33, which is read at all Orthodox weddings). This spiritual hierarchy is also reflected in the local parish presided over by the presbyter when he is assisted by his wife, the presbytera.3 Such complementarity is not a denigration of one sex or the other, but both man and woman are equally beloved by God and redeemed in his Son.

Living Sacrifices

Although only some are called to be priests, all are called to offer their own lives to God. “I beseech you therefore, brethren,” St. Paul writes, “by the mercies of God, that you present your bodies a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable to God, which is your reasonable service” (Rom 12:1). To live according to agapē is to live self-sacrificially, always obeying those twin commandments of love for God and love for our fellowman. “Love is a holy state of the soul,” St. Maximus writes, “disposing it to value the knowledge of God above all created things.”4 And he adds, “He who loves God will certainly love his neighbor as well.”5 St. Dorotheus of Gaza illustrates this dynamic using a geometrical image:

Suppose we were to take a compass and insert the point and draw the outline of a circle. The center point is the same distance from any point on the circumference [...] Let us suppose that this circle is the world and that God himself is the center; the straight lines drawn from the circumference to the center are the lives of men. To the degree that the saints enter into the things of the Spirit, they desire to come near to God; and in proportion to their progress in the things of the Spirit, they do in fact come close to God and to their neighbor. The closer they are to God, the closer they become to one another.6

Like traveling down the spokes of a wagon wheel towards the hub, we simultaneously learn to love our fellowman as our love for God grows.

Footnotes

-

The “Anaphora” (meaning, “to offer up”) is the central part of the Divine Liturgy, in which the celebrant offers up the gifts of bread and wine to God, asking him to sanctify them and return them to us as his true presence (the Body and Blood of Christ, the Eucharist). ↩

-

Anaphora of the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. ↩

-

The term “presbyter,” meaning “elder,” is the official title of a priest. In the Byzantine tradition, the wife of a priest is called “presbytera,” pointing to her role in assisting him in his ministry. In Romanian, the priest’s wife is called “preoteasa,” and in Arabic “khouria,” meaning the same as “presbytera.” In the Russian tradition, the priest’s wife is called “matushka,” meaning “little mother,” showing again her complementarity with the “batushka” (father). ↩

-

Maximus the Confessor, Four Centuries on Love 1.1, 164. ↩

-

Maximus the Confessor, Four Centuries on Love, 1.23. ↩

-

Dorotheus of Gaza, Discourses and Sayings, trans. Eric Wheeler (Kalamazoo: Cistercian, 2008), 138–9. ↩