A Rival to God

The scriptures are also quite clear that the world is a rival to God and a threat to the Christian’s loyalty to God. For this reason, Christian moralists have always warned the faithful against the spiritual dangers which come from the World, the Flesh, and the Devil. By “the World” (usually capitalized) is meant not the planet and its inhabitants, but the systematic and ingrained preference for the things of the world over a preference for the things of God.

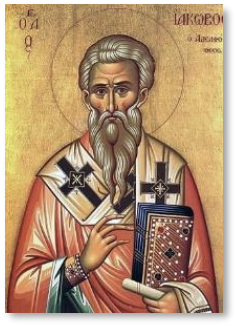

St. James warns in stark terms, with all the fire of an Old Testament prophet, of the dangers of preferring the world to God: “You adulteresses, do you not know that friendship with the world is hostility toward God? Therefore, whoever wishes to be a friend of the world makes himself an enemy of God” (James 4:4). St. John offers his own warning:

Do not love the world, nor the things in the world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him. For all that is in the world, the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the boastful pride of life, is not from the Father, but is from the world” (1 John 2:15-16).

This brief Johannine list of all that is in the world—the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes (i.e., a covetous desire to acquire and possess), and the boastful pride of life (i.e., the arrogance that ruthlessly competes, and struts, and shows off)—reveals that “the World” is complex and varied. What is common to all worldly elements is that each one seeks to claim and captivate the heart, to become an idol, and thus take the place of God in one’s life. That is why St. Paul referred to greed as “idolatry” (Col 3:5), because the grasping desire to acquire means that those things have usurped the place of God in one’s life. It is for this reason too that the Lord Jesus depicted wealth as “Mammon”—a divine rival to the true God (Matt 6:24).

There are dark aspects to some things in the world—or, perhaps more accurately, everything in the world is capable of great darkness. The lust of the flesh can present itself in the form of pornography in its many horrifying forms, as well as prostitution and human trafficking. The lust of the eyes with its desire to acquire can lead to many forms of fraud, lying, and theft as the desire to acquire money triumphs over the voice of conscience in comparatively mild crimes such as shoplifting, or more serious offences such as scams and identity theft.

It can also lead to the oppression of workers, the sin so often and furiously denounced by the Old Testament prophets who rebuked the elites for enriching themselves by grinding the face of the poor (see Isa 3:15). St. James stood in this tradition when he warned,

Come, you rich, weep and howl for your miseries which are coming upon you! Behold, the pay of the laborers who mowed your fields and which has been withheld by you cries out against you, and the outcry of those who did the harvesting reached the ears of the Lord of Sabaoth. You have lived luxuriously on the earth and led a life of wanton pleasure; you have fattened your hearts in a day of slaughter. You have condemned and put to death the righteous man; he does not resist you” (James 5:1–6).

The lust of the eyes and the boastful pride of life can lead one to do terrible things.

The sin denounced by James is common to all cultures, whether agrarian or urban. We see this sin in the faces of all corrupt politicians, all lying and conspiring CEOs, all the elite with power and wealth who manipulate media and rulers to their own advantage. The figure of such elites is common in the Psalter, where Yahweh promises to judge them thoroughly and vindicate the helpless widow and orphan whom they have despoiled and trampled. It is common for such worldliness to hide itself behind a mask of respectability, affability, and even piety. In this age, this 1% is rarely called to account by the other 99%. “There are no pains in their death… they are not in trouble as other men” (Psalm 73:4-5). They indeed live luxuriously on the earth and lead lives of wanton pleasure.

Faced with this, one is tempted to say quietly to oneself, “Surely in vain I have kept my heart pure and washed my hands in innocence” (Psalm 73:13). The temptation to learn from worldly men and their prosperity, to abandon one’s integrity and faith for the sake of gain—in other words to become worldly—is very great, which is of course why the psalmists, prophets, and apostles denounce it so regularly.

Being a Sojourner

The alternative to becoming a friend of the world is to recognize that one belongs to the age to come, and that here in this age we are sojourners and strangers, men and women just passing through this world on our way to the world to come. As sojourners, we abstain from the fleshly lusts which wage war against our souls and threaten to transform us into God’s enemies (1 Pet 2:11; James 4:4).

The world around us will challenge us if we renounce its way and choose a different way of living, correctly concluding that by our way of life and our choices we are judging and condemning them. Thus in 1 Peter 4:4 we read, “They [your former worldly friends] are surprised that you do not run with them into the same excess of dissipation, and they malign you.” The perception of the wicked and worldly that the righteous are a judgment upon them (whether or not the righteous say anything) is very old. Thus, in Wisdom 2:12–19 we read,

Let us lie in wait for the righteous man, because he is inconvenient to us and opposes our actions; he became to us as a reproof of our thoughts; the very sight of him is a burden to us, because his manner of life is unlike that of others. We are considered by him as something base, and he avoids our ways as unclean. Let us test him with insult and torture, that we may find out how gentle he is and make trial of his forbearance.

Worldliness is therefore not only a temptation. Avoiding it can be socially and sometimes even physically dangerous.

Christians are called to avoid such worldliness regardless of the dangers which such avoidance might bring. We must remember that such worldliness is indeed fading. We have a choice: either the pleasure of the world which is confined to this life, and which passes away, or the pleasures at the right hand of God which will never fail (Psalm 16:10). The Lord Jesus pointed out the inequality involved in the options: “What shall it profit a man to gain the whole world and forfeit his soul?” (Mark 8:36). The Faustian bargain proffered by the world is the fool’s bargain.

The apostles make this clear time and time again. St. John wrote, “The world is passing away, and its lusts, but the one who does the will of God abides forever” (1 John 2:17). St. Paul wrote, “The form of this world is passing away” (I Cor 7:31). Because of this, Paul gave more detailed advice about how the Christian was to live in this passing world. He said,

The time has been shortened, so that from now on those who have wives should be as though they had none; and those who weep, as though they did not weep, and those who rejoice, as though they did not rejoice, and those who buy, as though they did not possess, and those who use the world, as though they did not make full use of it (1 Cor 7:29–31).

This last bit of Paul’s advice is the key to living as sojourners and strangers.

St. Paul means that whatever we do in this world—whether marrying, weeping, rejoicing, or buying—we must do realizing that we could leave this world at any moment, and we must therefore find our true rest and joy in the Kingdom, and not in anything in this world. We indeed take joy in marriage and in buying and in all the others gifts that God gives us in this age. But as we use the world, we must not make use of it as if all our joys were anchored in it. We must be prepared to leave them all in a moment’s notice, if Christ so wills. The significance of Paul’s words for those possibly facing martyrdom is only too plain, but it retains its significance for all Christians who know that here we have no continuing city (Heb 13:14).

Read more: The World and the Flesh (opens in a new tab), Sin (opens in a new tab)