The Lives of the Saints

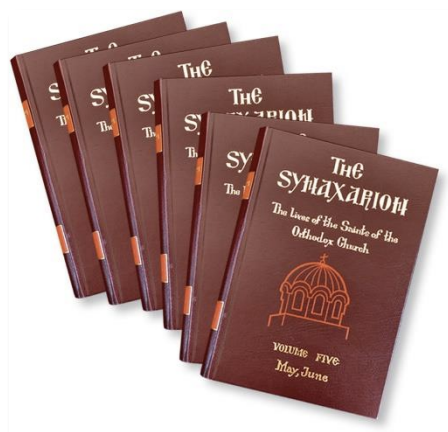

The hymns of the day which are sung at the Divine Liturgy usually include hymns to the saints of the day (who are also commemorated by name at the final dismissal). One finds the stories of the lives of these saints in a book called the Synaxarion, so-called because the stories of the saints were read at a synaxis, an assembly when the monks came together for Matins. The project of collecting stories of the saints began very early in the Church. Simeon Metaphrastes began a compilation of saints’ lives in the tenth century, and the project continued to develop after that. It is now contained in a collection of books, usually twelve in number, one volume for every month of the year. Each volume contains the stories of the saints who are commemorated that month.

These stories offer a unique combination of history, sermon, and tradition, all mixed together for a popular audience. In the words of the introduction to our present Synaxarion written by Hieromonk Makarios of Simonos monastery of Mount Athos, “The Synaxarion is like a great river, whose rushing water carries along mud, stones, branches, and a little of everything they have met with on their way, regardless of its value, but whose stream is life-giving.”1

“The Synaxarion is like a great river, whose rushing water carries along mud, stones, branches, and a little of everything they have met with on their way, regardless of its value, but whose stream is life-giving.”1

No one should imagine that veneration of the saints necessitates believing that St. George fought with an actual dragon or that St. Simeon was one of the translators of the Septuagint, still alive when he met the Holy Family in the Temple 270 years later. The stories in the Synaxarion are not offered merely as historical facts, but as a way of glorifying a saint whom the people love, and of holding up their virtuous lives for imitation. In the Byzantine hagiographical tradition, each story of the saint begins with the title, “The Life and Conduct (in Greek, the bios and politeia) of Saint N.” Note that with the latter word, politeia, the hagiographer’s concern is with how the saint lived in such a way as to glorify God. He wrote not as an historian, but as a pastor, with the sanctification of his readers as his main goal. The Synaxarion therefore serves two main purposes: that of praising the saint (and thereby recognizing God’s grace and power in his life), and that of offering an example to the faithful who read about his life.

First, reading the lives of the saints is our way of praising them, and thereby of integrating them into our lives today. The saints are not simply figures in history with no current relevance to our lives (like Julius Caesar or Napoleon), but fellow members of our parish family. As we ask for their prayers, we nourish and maintain our connection with them. St. John Chrysostom, for example, is not simply a bishop who lived a long time ago in Antioch and Constantinople. He is our friend who loves us and prays for us, whose writings we read, and whose liturgy we celebrate. Like all friends, he is a part of our life. Without the readings from the Synaxarion, the saints would retreat from us into the distant mists of history. And without the stories of the saints, the Church would have fewer examples of righteous living. Moreover, our own lives would be all the poorer without our friends who pray for us in heaven, cheering us on as part of the great cloud of witnesses. Our hymns to them in the church services and the stories of their exploits preserve a place for them in our hearts.

Second, the saints offer us examples of how we are to live. We need such examples of heroism and sanctity. Christians need Christian exemplars, people to imitate who model what it means to be a disciple of Jesus. In this way, we may consider the saints as Christian celebrities—men and women who by their politeia reveal what is truly valuable in life and how we should then live.

We see this approach to the saints as early as the Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 787 A.D., which set its seal on the restoration of icons in the church. A previous iconoclastic council had declared that it was useless to paint icons of the saints. Christians, they argued, did not need to see the fleshly faces of the saints; they merely needed to imitate their virtues. In answer to this argument, the Second Council of Nicaea replied,

We do not praise the saints, nor do we represent them in painting because we like their flesh. Rather, in our desire to imitate their virtues, we re-tell their life stories in books and depict them in iconography, even though they have little need to be praised by us in narratives or to be depicted in icons. Yet, as we have said, we do this for our own benefit. For it is not only the sufferings of the saints that are instructive for our salvation, but also this very writing of their sufferings.2

According to this ancient approach to the saints’ lives, these stories have benefit for us because they “are instructive for our salvation.” As we hear the stories of the saints’ exploits, their courage, serenity, wisdom, and holy defiance, we gain knowledge of how we are to act when faced with similar challenges. What mattered to the saints was not “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” but “the Kingdom of God and His righteousness” (Matt 6:33), and by taking the saints for our heroes, we also accept their approach to what our life goals should be.