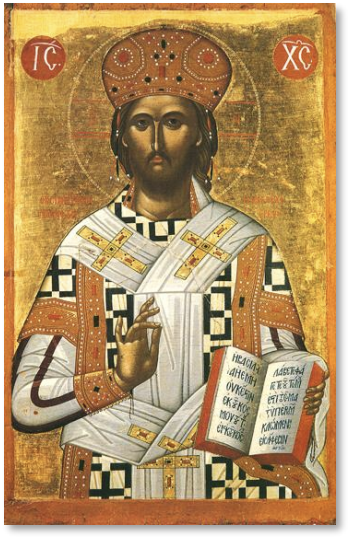

Christ the High Priest

The role of every priest is to bind heaven and earth through his intercession and offerings. In this sense, a priest is a mediator between two parties: representing the people as they reach upward towards God, and then representing God as he responds to his people. But the priesthood of Jesus Christ is entirely unique, being his very identity:  “For there is one God and one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus” (1 Tim 2:5). Through the incarnation, the divine and created realities are brought together in a union “without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.”1 And thus, mankind is reconciled to the Father in the very person of the eternal Son who “became flesh and tabernacled among us” (John 1:14).

“For there is one God and one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus” (1 Tim 2:5). Through the incarnation, the divine and created realities are brought together in a union “without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.”1 And thus, mankind is reconciled to the Father in the very person of the eternal Son who “became flesh and tabernacled among us” (John 1:14).

Because he is fully man, Christ is able to intercede for humankind as our high priest and “make expiation for the sins of the people” (Heb 2:17). His priesthood is not an earthly time-bound one like that of Aaron, as the apostle tells us in Hebrews, but rather an eternal priesthood foreshadowed by the mysterious Melchizedek (Gen 14:18-20; Psalm 2:7). Whereas the Aaronic sacrifices could never truly remove the sins of the people (hence the necessity of repeating it annually on Yom Kippur), the atonement of Jesus was made “once for all when he offered himself up” (Heb 7:27). And with his ascension into the heavens and seating at the right hand of the Father, he enters into the heavenly Holy of Holies to realize an “eternal redemption” (Heb 9:12), thereby opening the door to paradise to those who are “sprinkled by his blood” through the sacraments of baptism and reception of the Eucharist. St. Cyril of Alexandria writes, “For finding us as discarded and living outside of the holy and blessed city, meaning the Church of God, Christ came to us bearing our image. And examining us, he cleansed us through holy baptism and by his Body.”2 For those who enter into this new covenant in his blood, and thereby become members of his body, the Church, Christ is able to release them from the power of sin, death, and corruption by uniting them to himself, because “both he who sanctifies and those being sanctified are all one” (Heb 2:11).

In this context, we are reminded again of the prayer said prior to the Great Entrance by the bishop or priest serving the Divine Liturgy: Jesus Christ is referred to as both “the offerer” and the one being sacrificed, “the offering”.3 But this prayer also affirms that Jesus is also “the receiver,” the one to whom the offering is made. This is because the Son of God exists eternally as one essence with the Father and the Holy Spirit. Although it is only the Son who has assumed flesh, and who has become our high priest and the “one mediator between God [the Father] and men” (1 Tim 2:5), he is never separated from the other two Persons. Throughout the Scriptures and within the life of the Church, we witness all three persons of the Trinity acting in perfect unity to accomplish our salvation.

Sanctification

As we have seen, the priesthood of Christ is the bridge between the eternal, infinite life of God, and the limited, physical life of human beings. In becoming one of us, and therefore sanctifying his human nature, Christ made it possible for us to experience his divine life by grace (a freely-offered gift from God that transforms the recipient). From the moment of his conception in the womb of the Holy Virgin and Theotokos Mary, Jesus divinized the human nature he made his own, and by extension he began to sanctify the whole of creation. We see this demonstrated in his earthly life by signs and wonders, and by the fact that “power went out from him” (Luke 6:19) when others touched his garments. Entering into our reality, God again proclaims the world to be good, and begins to cleanse it of the spiritual pollution that has held it in bondage for so long (Rom 8:21). In Christ, every stage of human life is sanctified—from conception, to infancy, to youth, to adulthood. And likewise, the world he encounters is sanctified by his presence. We see this most clearly in the early Christian interpretation of Theophany, commemorating Christ’s baptism in the Jordan. For ancient peoples, water could symbolize either life or death: we need water to live, but often it becomes a destructive force in the form of storms, floods, and turbulent seas. It was also thought to be the abode of monsters and foul spirits who ruled over it. By entering into the waters of the Jordan, Jesus does not need to be cleansed, as he himself is the source of life and regeneration. Rather than being cleansed, he cleanses the waters, causing the pagan gods of the river and sea to turn back (see Psalm 113[114]:3). As St. Gregory of Nyssa preached, “For Jordan alone of rivers, receiving in itself the first-fruits of sanctification and benediction, conveyed in its channel to the whole world, as it were from some fount in the type afforded by itself, the grace of Baptism.”4 Theophany shows us the Trinity beginning to wash the world of corruption, an act made personally manifest in our own baptism, and also expressed through the blessing of Holy Water in the Church on January 6. This ongoing act of renewal will only come to fruition in the age to come, when a “new heaven and new earth” (Rev 21:1) will finally be revealed.

We witness this sanctification of the universe in a more personal way in the Divine Liturgy. At the consecration of the Eucharist, the presiding clergyman stands in the place of Christ the high priest, offering gifts on behalf of the people; and the Trinity receives this offering as a representation of our entire lives. Yet God does not need our gifts (he is free of all necessity). Rather, he blesses and sanctifies the bread and wine, changing them into his presence—the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ. In this way, the Son of God is also “the one distributed” in the Eucharist.5 In receiving these gifts, the faithful are united to God and each other in the most intimate manner: “The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not the communion of the Blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not the communion of the Body of Christ? For we, though many, are one bread and one body; for we all partake of that one bread” (1 Cor 10:16–17). Thus, the Eucharist becomes the “medicine of immortality,” the means by which God’s eternal life is made real in the body and soul of a Christian.6 St. Irenaeus explains,

and the Trinity receives this offering as a representation of our entire lives. Yet God does not need our gifts (he is free of all necessity). Rather, he blesses and sanctifies the bread and wine, changing them into his presence—the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ. In this way, the Son of God is also “the one distributed” in the Eucharist.5 In receiving these gifts, the faithful are united to God and each other in the most intimate manner: “The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not the communion of the Blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not the communion of the Body of Christ? For we, though many, are one bread and one body; for we all partake of that one bread” (1 Cor 10:16–17). Thus, the Eucharist becomes the “medicine of immortality,” the means by which God’s eternal life is made real in the body and soul of a Christian.6 St. Irenaeus explains,

For we offer him of his own, announcing consistently the communion and union of the flesh and Spirit. Far as bread, which is produced from the earth, when it receives the invocation of God is no longer common bread but the eucharist—consisting of two realities, earthly and heavenly—so also our bodies, when they receive the eucharist, are no longer corruptible, but have the hope of the resurrection unto eternity.7

It is in the midst of the Liturgy, reaching its climax with the reception of the sacrament, that the people of God participate in the priestly action of Jesus Christ.

Footnotes

-

Tome of Chalcedon in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers,14:264–5 ↩

-

Glaphyra in Patrologia Graeca. Ed. J. P. Migne. (Paris: 1857–1866), 69.560. ↩

-

Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, Prayer during the Cherubic Hymn. ↩

-

St. Gregory of Nyssa, Homily on the Baptism of Christ in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 5:522. ↩

-

Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, Prayer during the Cherubic Hymn. ↩

-

St. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Ephesians in The Apostolic Fathers, ed. and trans. Michael Holmes (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1990), 151. ↩

-

Against Heresies 4.18.5 in Anti-Nicene Fathers: Fathers of the Third Century, Vol. 4, ed. Philip Schaff, (Edinborough, 1890), 1:486. ↩