The Living God

Very often the popular concept of God savors more of deism than of theism. In popular thought God remains confined safely in heaven, happily isolated from life on earth.

From this distance He can sometimes answer prayer, and we console ourselves with the thought that our beloved dead whom we mourn go to be with him in heaven when they die. But for all that God is not really involved in life down here on earth, however often we describe freak lightning strikes and floods as “acts of God.” God never judges or directs the affairs of history. He never really intervenes. He mostly just watches and waits.

In contrast to this is the biblical picture of God as “the living God,” the phrase which emphasizes Yahweh’s1 power to act compared to the powerless idols of the heathen (Psalm 114[115]:1–8). The gods of the nations are dead, lifeless, unable to smite or to rescue, or to do anything. They can neither judge and strike down, nor restore and raise up. But Yahweh is the living God, the One who judges the wicked and rescues the righteous, who executes justice for the oppressed, who gives food to the hungry, who raises up those who are bowed down, who brings to ruin the way of the wicked (Psalm 145[146]:7–9).

The title “the living God” is Jewish code for God’s continual and powerful involvement in the world He has made, in contrast to the idols. Thus St. Peter confessed Jesus to be “the Christ, the Son of the living God” (Matt 16:16); thus St. Paul reminded the Thessalonians that in their conversion they had “turned to God from the idols to serve a living and true God, and to wait for his Son from the heavens” (1 Thess 1:9,10).

This God is not the deity of the deists, nor the God of the philosophers. He is powerful, active, saving, compassionate—and dangerous. Too dangerous, in fact, for most people, and so popular imagination cuts him down to size. Popular imagination confines him to heaven, chaining him to his celestial throne, denying him access to earth. Everything that occurs down here has only natural causes; everything must be explained by something— anything—other than the work of the living God.

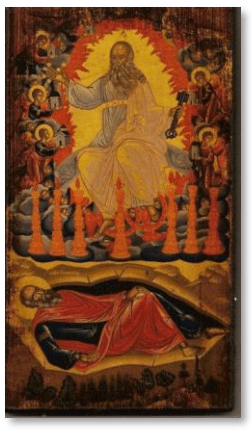

Christian theology knows nothing of this little God. Our faith remains rooted in the living God revealed in Christ, who manifested his power through the cross and resurrection of his Son, and who continues to work among us through miracles and the sacramental life of the Church. The true and living God is not safe and not tame.2 his very presence causes trembling: when Isaiah saw Him in the Temple, he declared himself undone; when St. John saw Him in a vision, he fell at his feet as one dead (Isa 6:5; Rev 1:17).

This God existed before the world was made, and by his power brought all things into being. He is transcendent, above and beyond all created things—yet He fills all things— and is present in every atom of his creation. This is not pantheism, which declares that impersonal divinity is in everything and that therefore everything is divine. It might be described as “pan-en-theism”, which asserts that the personal and transcendent God is found in all that exists, so that no corner of the cosmos is bereft of his presence.

Part of the theologian’s task is to speak of God and to describe him. The task is an impossible one, for God surpasses all description, all thought, all imagination, and every category we might conceive, including the binary categories of being and non-being. That is why the theologian known as (Pseudo) Dionysius in about the fifth or sixth century strained the limits of language in an attempt to describe the indescribable. The proper response to an encounter with the living God is mute wonder and ecstatic adoration. Yet the Church must still teach about this Lord, and so theologians have done their best to find words that are the least inappropriate to describe God. No one can describe him accurately; the best we can do is to use words which, whatever their inadequacy, offer the least distortion, all the while knowing that God remains above such descriptions. An apophatic approach3 may be best for solitary mystics, but life on earth and the Church’s mission demand the use of a cataphatic approach4 as well. Thus, a number of terms are used to describe the living God.

One of these terms is “omnipotent”, or all-powerful. This means that whatever God chooses to do, He has the power to accomplish. There is no task that He chooses to undertake which might prove too much for him. But here a note of clarification must be offered—divine omnipotence does not mean that God can somehow do things which are intrinsically impossible, such as making two plus two equal five, or giving free will to men while simultaneously withholding it. As someone once wrote, “Meaningless combinations of words do not suddenly acquire meaning because we prefix to them the two other words ‘God can’… Nonsense remains nonsense even when we talk about God.”5 Or, in the words of Thomas Aquinas, “Nothing which implies contradiction falls under the omnipotence of God.”6

God is also omnipresent. God’s transcendence (in biblical terms, his throne in heaven) does not imply that He is distant from any part of his creation. He is no closer to those on mountaintops than He is to those underground. He is not spatially closer to those in church than He is to those in the trenches of war. One draws near to him through repentance and faith, not through physical movement. That is why St. Paul affirmed that in him we live and move and have our being, and that He is not far from anyone (Acts 17:27–28). God is everywhere. We approach him with our heart, not with our feet.

Christian theology confesses that God is also invisible, and that the visible appearances of God in the Old Testament, such as when God was seen on Mount Sinai, by Isaiah in the Temple, and by Ezekiel by the river Chebar (Ex 24:9–10; Isa 6:1; Ezek 1:26–28) were theophanies. In those appearances, God was condescending to human weakness, appearing to Israel in human form (Ezek 1:26) so that Israel might more easily communicate with him. But strictly speaking, God has no body, no parts, no form. He is invisible, so that no one has ever seen him or ever can see him (John 1:18; 1 Tim 6:16). He can appear to us in a vision (e.g., Dan 7:9; Rev 4:2–3), but the reality is higher and more transcendent than the vision. Being above every category and conception and filling all things, God cannot be seen. He is incomprehensible, not just to men and angels, but in Himself.

God is also eternal, and not subject to time as we are. He does not move from the past into the present and then into the future but exists above the limitations of time and space. This does not mean that in his dealings with us He does not respond to us in the moment and deal with us where we are. In his condescension, the One who is eternal and beyond time, the One for whom there is no past, present, or future, but who lives above the flow of time, stoops down to speak with his creatures who do live within the flow of time and who experience change.

present, or future, but who lives above the flow of time, stoops down to speak with his creatures who do live within the flow of time and who experience change.

We see these time-conditioned interactions in the scriptures: God announced to Nineveh that He would destroy them for their sins, and then “changed his mind” after they repented (Jonah 3:10). This does not mean that God was somehow surprised at their repentance, as if He did not know beforehand what would happen. But God dealt with them where they were and responded to their actions accordingly. We are children of time, and experience things sequentially within the flow of time, not knowing what the future will bring. In order to have a relationship with us, God speaks to us where we live within this flow of time, even if He knows all that will happen before it does.

Furthermore, God is immutable, and not subject to change. This means that God is not affected and limited by external circumstances. Things impact us and cause us to change—either to grow or to decline. We are usually passive in our lives, in that disasters can hurt us and make us sad or bitter and successes can cause us to cheer up and increase in happiness. Our moods and life exist in this state of flux and change, as we are at the mercy of things in the world around us. God is not like this at all. He is not at the mercy of circumstances, and there is nothing passive in him; in Himself He cannot be made depressed or more cheerful.

Despite this, God condescends to us in our weakness. That is why in the Scriptures we read of God becoming angry when Israel sinned by worshipping Baal-Peor, and of God calming down when Phineas stood up to punish Israel’s sin (Num 25:3, 11). This anthropopathic7 way of speaking about God was the only one possible if Israel was to have a relationship with the changeless God.

Finally, we note that God’s essence is different from his energies. By God’s essence is meant God as He is in Himself; by his energies is meant how we experience God. The distinction between his essence and his energies preserves the transcendent nature of God while at the same time declares that we can really know and experience him, for his essence is present in his energies.

In all these theological descriptions the Church does not seek to define God or fully describe him, for it knows this is an impossible task. Rather, these cataphatic terms are attempts to safeguard the nature of the living God from distortions and from understandings that are unworthy of him. Each Christian encounters the living God in humility, approaching him with fear and love and trembling. God is only known by us because in his compassion He allows Himself to be known and experienced.

Read more: The Doctrine of the Holy Trinity (opens in a new tab), One God: One Divine Action and Will (opens in a new tab), God (opens in a new tab)

Footnotes

-

The name "Yahweh" is used by some to represent the Hebrew Tetragrammaton (meaning four letters) יהוה (Yod Heh Vav Heh). It was considered blasphemous to utter the name of God; therefore, it was only written and never spoken, resulting in the loss of the original pronunciation. It is more common in English-language bibles to represent the Tetragrammaton with the term "LORD" (capitalized). ↩

-

Compare the Christological description of Aslan in C. S. Lewis’ The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (NY: Harper Collins, 1994), 80. “Safe? Who said anything about safe? ’Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.” ↩

-

Describing what God is not ↩

-

Describing what God is ↩

-

C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain (NY: Harper Collins, 1996), chapter 1. ↩

-

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Part I, Question 25, article 4. ↩

-

The use of limited human language to describe God’s actions. ↩