Naming

To “name” something or someone has a long tradition in the Scriptures and in Holy Tradition. It is a solemn act of recognition that has several aspects. First, there is the idea of “naming” in order to show mastery, though of an intimate and benign kind: we see this in Adam’s naming of the animals who are brought to him by God (Gen 2). Conversely, the “Man” who wrestles with Jacob in Genesis 33:22–32 will not tell Jacob his divine name but gives Jacob a new name. As Fr. Schmemann reminds us, naming “reveals the very essence of a thing…its essence as God’s gift,”1 Of course, it is the greater one, the one with a fuller perspective, who can see this essence in the lesser one, and so properly bless him or her. We should then be astonished that Christians, unlike the Jewish people before them, are invited to “name” God as Father, and we are “bold” to do that because we are in Christ, adopted sons and daughters. In this case, the naming is a privilege, an indication of our intimacy with God, and not of our power over him, or ability to see all that He is! Amazingly, God has called us to “bless” him as the Lord, and as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, though usually it is the role of the one who is greater to bless those under him (Heb 7:7). Such is the humility of God: but we remember all this when we bless and name him, knowing that He has made us worthy to do so.

As Fr. Schmemann reminds us, naming “reveals the very essence of a thing…its essence as God’s gift,”1 Of course, it is the greater one, the one with a fuller perspective, who can see this essence in the lesser one, and so properly bless him or her. We should then be astonished that Christians, unlike the Jewish people before them, are invited to “name” God as Father, and we are “bold” to do that because we are in Christ, adopted sons and daughters. In this case, the naming is a privilege, an indication of our intimacy with God, and not of our power over him, or ability to see all that He is! Amazingly, God has called us to “bless” him as the Lord, and as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, though usually it is the role of the one who is greater to bless those under him (Heb 7:7). Such is the humility of God: but we remember all this when we bless and name him, knowing that He has made us worthy to do so.

Naming the Saints

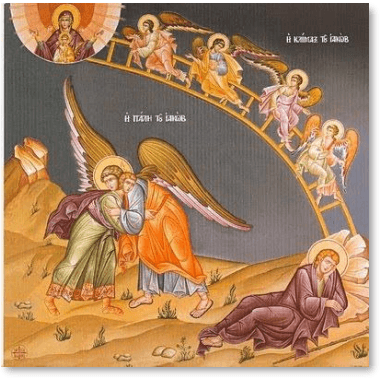

When we name other people, it seems that this is a naming that is different both from the custodial naming of animals, and the extraordinary naming of God: it is a kind of “lateral” blessing that we extend to brothers and sisters in Christ, some of them far more gifted than we. And the blessing is interconnected both with our trust in God’s great generosity, and our thanksgiving for all that He has given, is giving, and will give. When at the Anaphora we name the Theotokos and the other blessed who have come before us, we express our solidarity with them, and the rich corporate nature of our whole life in Christ. We cannot control those blessed whom we name, nor their circumstances, and so when we name them, we do so with awe, in a kind of utterance that is closer to our audacious blessing of God than to Adam’s naming of the animals. We know them, and presume, indeed, that they know us better than we know them. In our personal prayers, we are coming to know these blessed ones better and better, and so we celebrate the wonder that they are with us around the table of the Lamb. They are with us, and we remember that.

Our prayers for our living bishops, priests, and friends are attended by the same awe, as we remember all that God is doing in our midst. We acknowledge those who are not with us physically, but to whom we are joined in this act of Thanksgiving. Naming is a natural thing for the Church of God. Consider that we name babies and new converts in their baptisms, showing the same wonder and intimacy. It is not as though God needs to be introduced to these dear ones, or reminded of them: after all, He knew them before, knows them after, knows them in a far deeper way than we do. But such is the nature of the Christian family that we are instructed to pray for them, and even for those who have not yet joined us:

Therefore I exhort first of all that supplications, prayers, intercessions, and giving of thanks be made for all men, for kings and all who are in authority… for this is good and acceptable in the sight of God our Savior, who desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth” (1 Tim 2:1–4).

Our prayers for each other, then, are a natural part of our life together. The Eucharist, while a deeply personal time between each of us and the Lord, is also a means of drawing us closer together, reflecting the deep, organic connection that we have with one another as the Body of Christ.

Remembrance of others, and intercessory prayer for them, proceeds on the foundation of an absolutely unique God, who is generous to all, and who invites us to participate in this generosity when we pray for each other, and even for those outside the household of faith. The letter to the Galatians speaks of prayer for other Christians as a supremely important act, while also giving us a salutary reminder of our temporality. Even our participation in timely action is important to God: “Since, then, as we have this present moment, let us do good things for all, and especially for those who are in the household of faith” (Gal 6:10). The word used to refer to the “present moment,” kairos, is the same Greek word that is used when the deacon reminds the priest, “It is time for the Lord to act,” at the beginning of the Divine Liturgy. God, of course, superintends all of time, but frequently in the gospels and the epistles emphasis is put upon the time in which we now stand, the present moment—for that is, as humans, what we possess. The past flees away and the future we cannot know: but God has given to us this moment, and has entered into it in His Son, who accepted our human limitations, for our sake. It may even be that during the Divine Liturgy we are given even more than an ordinary present moment, for in Christ we have been transported into the heavenly Kingdom.

God knows and fills the whole sweep of time, and Himself is the supreme judge regarding how best to act in the moment. Standing beside his throne, we have a more certain knowledge of the large picture (shown to us in Holy Scriptures, the Tradition of the Church, and the prayers of the ages), and are prompted to act at the right time—to pray, through the dwelling of the Holy Spirit among us. This present moment (kairos) is ours in which to act, and so we are instructed to “redeem the time (kairos), because the days are evil” (Eph 5:16) and reminded that “now is the acceptable time (kairos)” to act in harmony with the Lord (2 Cor 6:2; cf. Isa 49:8). As Jesus told his disciples before his death, we are no longer servants, but friends, because we know what the Father is doing (John 15:15). This insight concerning our position and our role is not intended to make us arrogant or presumptuous, but to move us to wonder. The Creator of all is including us in his loving action for the world.

Inclusion in this divine energy is expressed in a particularly beautiful way when we pray for each other, further strengthening the links that join together his household of faith. Consider what happens when one of us prays for another: that believer, praying in Christ, and through the Holy Spirit, brings his or her brother or sister, with that person’s own concerns, before the Father. Here we see true communion: the Holy Trinity, the prayer, the one being prayed for, and his or her own concerns (frequently other people), are all linked within the give-and-take of prayer. This is amplified when we pray in concert, together in the assembly of God’s people. In such prayer, we acknowledge Christ as the head of the Body, the power of the Holy Spirit, and the beneficence of the Father, whose will is that we should be one, as the Trinity is One. Our intercessions and remembrance at this time picture the very nature of the Church. Indeed, our prayer is an effective icon that does not simply represent, but also expresses and creates this unity to which we are called. The Church at prayer, then, is an icon of God that is a good in itself, just as marriage is a good in itself but shows forth the unity of Christ and the Church (Eph 5:31–32). As such prayers are offered, those who come into our midst will say, “See how they love one another!”

In such prayer, we acknowledge Christ as the head of the Body, the power of the Holy Spirit, and the beneficence of the Father, whose will is that we should be one, as the Trinity is One. Our intercessions and remembrance at this time picture the very nature of the Church. Indeed, our prayer is an effective icon that does not simply represent, but also expresses and creates this unity to which we are called. The Church at prayer, then, is an icon of God that is a good in itself, just as marriage is a good in itself but shows forth the unity of Christ and the Church (Eph 5:31–32). As such prayers are offered, those who come into our midst will say, “See how they love one another!”

Footnotes

-

Schmemann, For the Life of the World, 21. ↩