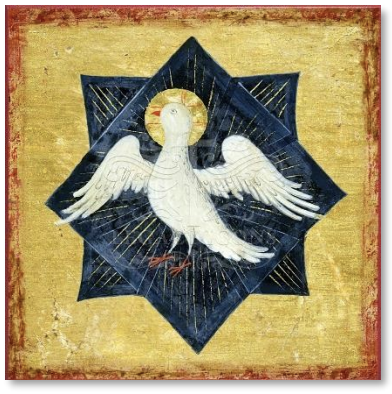

The Holy Spirit

The Spirit of God in the Old Testament

In the Hebrew Scriptures the Spirit of God is seen in Yahweh’s acts of power: the Spirit of Yahweh came mightily upon Samson, and he tore apart an attacking lion as one tears apart a young goat (Judg 14:6). The Spirit of Yahweh fell mightily upon Saul when he approached Samuel and his prophets so that Saul also stripped and fell down among them in ecstasy and prophesied for a day and a night (1 Sam 19:23–24). The Spirit of God enabled craftsmen such as Bezalel and Oholiab to produce beautiful work building the Ark and its furnishings (Ex 31:1f). It was the Spirit of God that filled the prophets and enabled them to receive the words of Yahweh.

The Hebrew word for spirit is ruach, which is also the word for breath and wind (compare its various uses in passages such as Ezekiel 37, where it means all three). ruach is therefore associated with life, based on the observation that when moving air ceases to flow from a body, the person is dead. A person’s ruach is his life; when his ruach departs, he dies.

We find this identification of ruach with life in such passages as Psalm 104:29–30 which describes the death of life in the winter and its renewal in the spring. There the psalmist says, “When You [Yahweh] take away their ruach, they die and return to the dust. When You send forth Your ruach they are created and You renew the face of the ground.”1 God’s ruach, his Spirit, is therefore the principle of his life, and it is through the action of his ruach that God acts with power to create and strengthen the world. Because this ruach is the ruach of Yahweh, the Holy One, St. Paul used the term “the Spirit of holiness” to describe him (Rom 1:4), as well as the more usual term “the Holy Spirit”.

The Spirit of God in the New Testament

It was this Holy Spirit that Christ promised his disciples that He would soon send upon them during his last night with them. The Spirit had been among them and in their midst during Jesus’ ministry when He did his works of power, but soon the Spirit would not just be among them, but in them (John 14:17). When the Spirit came, He would teach them all they needed to know and bring to remembrance the words Jesus spoke, enlightening the apostles to know their true meaning and to glorify Jesus (John 14:25–26, 16:14). This was fulfilled on the day of Pentecost when Jesus received the Spirit from the Father and poured him out upon his waiting Church (Acts 2:1–4, 33).

It is clear from other New Testament references to the Spirit that the Spirit is not an impersonal power or influence (like magnetic force or electricity), but a person. One can grieve the Spirit by sinful acts (Eph 4:30), and one can lie to the Spirit (Acts 5:3)— actions which presuppose interactions between persons. Thus, in the Book of Revelation the Spirit speaks, offering a blessing to those who die in the Lord, (Rev 14:13), and that book closes with a double invitation from the Church, the Bride of Christ, and from the Spirit, as both invite the hearer to “come” to salvation (Rev 22:17). That is why in Christ’s final words to his disciples He referred to the Spirit as someone whom He would send and who would perform various tasks when He came. The Spirit was a person, distinct from the Father and the Son.

That Spirit is the Spirit of the Father (see Matt 10:20), for He is the Spirit of Yahweh. But because Christ received the Spirit from the Father and poured him out upon His Church, the Spirit is also the Spirit of Christ (see Rom 8:8; Gal 4:6).

Footnotes

-

This is, I suggest, what was originally meant by Jesus’ word that the Spirit “proceeds from the Father.” The Greek of Isaiah 57:16 which speaks of God’s spirit “proceeding” from him refers to God’s acts of creation. ↩