Blessed is the Kingdom of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit…

The Church, though it sojourns on earth, therefore, lives in the Kingdom of God which is why each Orthodox Liturgy begins with a doxology blessing the Kingdom of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. The supernatural powers of rebirth, forgiveness, and spiritual transfiguration, received in baptism, Eucharist, and in all the sacramental rites of the Church, are manifestations of the Kingdom. Since the disciples of Jesus now participate in this kingdom, they are made God’s sons, his heirs, and they receive “the fulfillment of the Kingdom of heaven”1 every time they receive Holy Communion. Life in Christ involves our continual sharing in the power of the Kingdom, for which reason St. Paul wrote that “the Kingdom of God does not consist in words, but in power” and in “righteousness and peace and joy in the Holy Spirit” (1 Cor 4:20; Rom 14:17)—i.e., in a transfigured life.

This reality was early recognized by the Church Fathers. Late in the first century, St. Clement of Rome wrote to the Corinthian Christians, describing their liturgical experience by saying that “a full outpouring of the Holy Spirit was upon you all.” In their liturgical assemblies, the gathered Christians experienced the presence of the new aeon in the form of an outpouring of the Holy Spirit.

The Church is therefore the manifestation of the Kingdom of God on earth, for it is the presence of Jesus. As His Body and fullness (Eph 1:22–23), the assembled Church manifests the new aeon, the powers of the age to come. When the baptized disciples of Jesus gather together for the Eucharist, they become, in an exceptional and full manner, his Body, and Christ shines forth in their midst with all his power to forgive, heal, and transform. The Church is the presence of the future, the Kingdom of God here in this age in seminal2 form, representing that portion of the world which is even now in an ongoing state of transformation. That is why Philips’s apostolic preaching was described as “the good news about the Kingdom of God and the name of Jesus Christ” (Acts 8:12). St. Clement was reminding the Corinthians that through their sacramental gathering, their assembly, their ekklesia, or “church”, the Kingdom of God could be experienced in this age.

The Kingdom of God is therefore not of this world—i.e., it is not a kingdom like all the other kingdoms, presided over by an earthly king openly supported by military power and enforced taxation. God’s kingdom is not a country with borders to be guarded and secured, has no economy kept running by a workforce, no police, courts, or penal system as do all other kingdoms. It needs no diplomats to represent it, no treaties to sustain it, no wars to protect or expand it. This is what Christ meant when He told Pilate at his trial that if His Kingdom were of this world then his servants would be fighting (John 18:36).

It needs no diplomats to represent it, no treaties to sustain it, no wars to protect or expand it. This is what Christ meant when He told Pilate at his trial that if His Kingdom were of this world then his servants would be fighting (John 18:36).

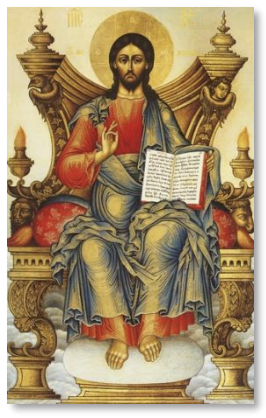

Christ rules His Kingdom from the Father’s right hand in heaven, transcendent above all the earth and its political and military machinations. His Kingdom rose when He rose to heaven, and unlike all earthly kingdoms (such as the Roman empire) it will never fall. Christians who are part of that kingdom have their citizenship in heaven (Phil 3:20) and belong to a kingdom safely beyond hostile human reach.

Israel in the first century did not know this about the Kingdom of heaven (although there were scattered hints in the prophets, such as Isaiah’s word that in the kingdom such formerly hostile nations as Egypt and Assyria would have the same status as did Israel (Isa 19:19–25)). Suffering under the brutal yoke of Rome, Jews longed for a kingdom that was of this world, and a messianic king that would spill Roman blood and destroy the Roman empire. They could not understand his parables correcting this mistaken view of the Kingdom of God, because that kingdom was not what they wanted.

In Jesus, God was bringing a new and different kingdom into being—and for Israel, an unwelcome one. Jesus was not the usual kind of king. He was a crucified king, a king who was glorified by being lifted up on the cross (John 12:23–24, 32–33), a king without a fighting army guarding a nation. This new kind of king, of necessity, brought a new kind of kingdom—and a new way of belonging to that kingdom.

Formerly, inclusion as part of God’s covenant people—and being heirs of God’s promised kingdom—was by circumcision, sabbath observance, and temple sacrifice. But the Kingdom was not built on national principles or a national foundation, but on spiritual ones, and so now inclusion as part of Israel was being reconfigured. Circumcision, sabbath, and temple sacrifice characterized them as a nation, but now membership in God’s covenant people was through discipleship to the crucified king— i.e., through baptism.

After Christ had been crucified as their king, inclusion in the covenant people of Israel no longer involved circumcision, sabbath, or temple sacrifice (“works of the law”). Now union with Jesus alone was required. After the cross and resurrection, Jews were invited to enter the Kingdom, a new transcendent, trans-national kingdom, through baptism and discipleship to Christ. If Christ were a king like any other king and His Kingdom were a kingdom or nation like any other, such a reconfiguration of membership in Israel would not have been required. But a crucified Christ changed everything. Now participation in Israel is through baptism, so that the Church is “the Israel of God” (Gal 6:16). The Church inherits Israel’s promises and destiny and enjoys the kingdom God promised to his people.

Read more: The Kingdom of God (opens in a new tab), The Kingdom of Heaven (opens in a new tab)