Thanksgiving

Unfortunately, when we use the term, “Eucharist,” some may be simply puzzled by a perplexing liturgical word borrowed from the Greek. When we translate it into the English, “Thanksgiving,” others may be put off by the sentimentality that surrounds this holiday in America, or be reminded of the saccharine sweetness of Pollyanna, who learned to play the “glad game” in order to displace a bad mood.1 Children of our pragmatic age, we are not likely to think of giving thanks as foundational to who we are as human beings. We are more likely to judge thanksgiving to be a matter of disposition, more natural to optimists than to pessimists or realists. Essential to human beings, we would assume, is thinking, caring for others, creativity, and the like. The giving of thanks, we might assume, cannot define who we are, or who we are meant to be, since it is related to situations and moods, and therefore variable. However, this approach forgets the deepest foundational truth about us: we are creatures made in the image of God, to whom we owe everything, and first of all, a debt of gratitude.

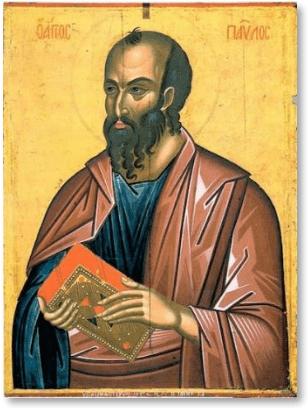

The inability to give thanks continually is thus not simply a dispositional quirk, or a wound on the jaundiced souls of some who have seen more sorrow than others. Rather, it is a human malady found everywhere, and fostered by a distorted view of where we are (in a good creation, Gen 1:4 ff.), who we are (made after God’s image, Gen 1:27), and whose we are (God’s own handiwork, Eph 2:10). Many have thought that the primal sin of Adam and Eve was pride, and there are good reasons for seeing radical selfcenteredness as close to the root of our problem. However, St. Paul tells the story of creation and the fall in such a way as to highlight our human refusal to worship and give thanks, and how that rebellion has infected every one of us:

For since the creation of the world His invisible attributes are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even His eternal power and Godhead, so that they are without excuse, because, although they knew God, they did not glorify Him as God nor were thankful, but became futile in their thoughts, and their foolish hearts were darkened. Professing to be wise, they became fools, and changed the glory of the incorruptible God into an image made like corruptible man—and birds, and four-footed animals, and creeping things…. [They] exchanged the truth of God for the lie, and worshiped and served the creature rather than the Creator, who is blessed forever. Amen. (Rom 1:20–25)

In this sequence, then, we see that God made the world so that it gives intimations of who He is— “His invisible attributes are…understood by the things that are made.” One of the innate characteristics of the creation is that it shows who God is. If we go back to the primal story of Genesis, we hear from God’s own lips what this “showing forth” entails. Of the creation, He said, “it is good” (Gen 1:4, 10, 12, 18, 21, 25); concerning the day on which he created humankind, He said, “It is very good!” (1:31). So, then, in looking at the creation itself, we see evidence of the goodness of God; in looking at humanity, we see evidence of the excellence of God. The created order, and especially human beings, are signposts, traces of God’s very nature.

But, of course, the purpose of a signpost is to point to something other than itself. Human goodness consists in being an icon of God, in mirroring the image and likeness of the Creator. Our sacred story of origins differs from both the early Mesopotamian myths, like the Enuma Elish (where humankind was made out of dragon’s blood to serve in slavery to the gods), and the contorted stories of the later Gnostics (where a rebellious demigod made humans, resulting in a decline from what was perfect and spiritual, into the imperfect material world). Clearly, those who composed such stories did not correctly read the signs imprinted in creation concerning a Creator who was both good, and who declared the material creation, in all its teeming variety, to be good as well. Nor did they understand that God’s intention for humankind is not to enslave, but to have intimate communion with us, and through us to cultivate and perfect the world that He has made: we are to be partners with him, what some have called sub-creators. This astonishing compliment paid to human beings is surely worthy of thanksgiving!

Footnotes

-

Eleanor H. Porter, Pollyanna (Boston: L.C. Page, 1913). Pollyanna became a byword for someone who is always optimistic and cheerful. ↩