The Christian Life: Living the Beatitudes

The life of the Christian worshipping the living God and following Jesus may be summed up in the Beatitudes. The Beatitudes form the prolegomena1 to the Sermon on the Mount in the same way that the Ten Commandments formed the introduction to the entirety of the Law. The contrast between Law and Beatitude is intentional: the ten commandments gave instructions for regulating the life of the theocratic community, but Christ bestows blessing in the coming kingdom. The former found its context in the national life of Israel in this age, whereas the latter finds its context in the eschatological reversal coming with the Kingdom of God. The former demands obedience: the latter assures reward for those who have served Christ. The difference here is the difference between the Law and the Gospel.

The reward promised in the Beatitudes consists of blessing in the age to come. The word usually rendered “blessed” is the Greek makarios, a word used in classical Greek to denote the happiness of the gods. In Christ’s day, the world looked at those poor, bedraggled souls who followed him, and thought them to be deluded, pitiable, and pathetic—a bunch of fools rightly to be met with disdain and a sorry shake of the head. This is what the Pharisees thought of Jesus’ disciples, writing them off and saying, “This rabble which does not know the law is accursed” (John 7:49).

In response to such denunciation, Christ assured his followers that they were not accursed, but blessed. A tremendous reward awaited them in the coming kingdom. The rich who despised them and who rejected Jesus will one day hunger and howl,2 but not his disciples. They will be filled and will laugh. On that blessed day of vindication, anyone might envy their fate. his disciples therefore must persevere in their faith despite the persecution their faith brought upon them. Their reward will be great in the age to come.

On that blessed day of vindication, anyone might envy their fate. his disciples therefore must persevere in their faith despite the persecution their faith brought upon them. Their reward will be great in the age to come.

But to live the eschatological life of the age to come and inherit those rewards, Christ’s people must live differently than those around them. They must imitate the Lord. This imitation is described in the Beatitudes in a series of word pictures.

The first of the word pictures portrays someone who is poor in spirit. This referred to a certain class of people found in the Psalter, the anawim, the afflicted, the humble, those oppressed and helpless before the rich and powerful of the world who crushed them (Psalm 9:18, 36:6, 72:2). These poor had no recourse to earthly help, so they placed all their hope in God, looking to him for rescue and vindication. It was these hopeless and helpless, these afflicted ones, these anawim, that God promised that He would one day vindicate; these are the Lord’s disciples.

However, to be poor in spirit means more than finding in God our hope of vindication. It also means despairing of saving ourselves and in finding in ourselves the strength we need. We are all weak. The poor in spirit acknowledge this and realize that without Christ, they can do nothing.

Christ also portrays those who follow him as those who mourn—that is, those who sorrow because their hard life is lived within a vale of tears. Such mourning is not pathological, it is simply a recognition that all is vanity, as the writer of Ecclesiastes tells us in his brief twelve-chapter treatise. This Beatitude proclaims that it will not always be so. Grief will not have the final word, nor will mourning last forever. If we follow Christ, our final state will be one of joy, not grief, and the mourning will give way to dancing and to laughter (Psalm 30:11; Luke 6:21).

Christ’s disciples are also characterized as the meek. The English word “meek” is not a happy word. It conjures up images of spinelessness, moral timidity, cringing subservience, and pathological faint-heartedness. No sensible and responsible parent would raise their child to be meek. Meek people are not psychologically healthy or able to withstand the rigors of life. This is not, of course, what the Greek word used here means. That word is praus, and it was the word used in the Septuagint Greek to describe Moses in Numbers 12:3. One recalls that Moses suffered from none of the timidity or cringing subservience usually associated with the English word “meek”. Moses stood defiantly before Pharaoh, head of the world’s greatest power, and boldly demanded that he let Israel go. Moses, after descending Mount Sinai with the Law of God in his hands, discovered Israel indulging in an orgy of idolatry around a golden calf. He broke the tablets of the Law, ground the golden calf to powder, threw it into the local water source and made Israel drink it. He then called upon volunteers to slaughter the apostates (Num 32). This does not sound at all like pathological faint-heartedness.

The Greek word indicates self-control, and the word is used to describe wild animals which have been tamed and domesticated so that they may be useful to man. A man who is at the mercy of his passions (such as uncontrolled anger) is not praus; a man who can control his impulses is. Christ is described as praus in Matthew 11:29. St. Paul commends this characteristic as a fruit of the Spirit in Galatians 5:23; St. Peter praises a praus and quiet spirit when found in wives in 1 Peter 3:4 as something very precious in God’s sight. Perhaps a better translation might be “gentle”. In a rough and tumble world, one might be tempted to push back aggressively, fearing that “nice guys finish last.” But Christ bids us be gentle and promises that such gentle souls will inherit the earth.

The next Beatitude commends the merciful. Long familiarity with our Lord’s words and Christian teaching generally have desensitized us to how revolutionary this teaching originally was. The world in the time of Jesus did not value mercy. Whatever rhetoric might occasionally be used in grand speeches by the powerful, at the end of the day mercy was equated with weakness. Rome could not afford to be seen as merciful.

This made Christ’s teaching even more astonishing (and politically dangerous) to ancient ears, for He consistently counseled such mildness in a way that struck men as perverse and criminally naïve. If a person delivered a public insult to you by slapping you across the face, you were to do nothing except offer him the other cheek for a second slap. If a man sued you and took your shirt, you were to let him have your coat too, as a kind of unforeseen gift. If a Roman soldier insisted on enforcing the letter of the law for those occupying a country and compelled you to carry his pack one mile, you were to carry it for another mile after that. For Christ’s disciples, the offering of mercy and forgiveness for offences were not to be occasional acts of moral heroism, but a way of life.

The disciple of Jesus must also be clean of heart (usually rendered as “pure of heart”). The Greek word is katharos. The word katharos has a slightly different feel and nuance than the Greek word for “pure” (agnos). The word katharos is used to describe the clean water used in the Law’s rites of purification (Heb 10:22), the clean linen shroud in which Christ was buried (Matt 27:59), and the clean state of those who have just bathed (John 13:10).

Our Lord’s words in this Beatitude have this concept of ritual cleanness as their background and were intended as a polemical response to them. Christ Himself had little time for the Pharisees’ obsessive concern with possible ritual contamination (Mark 7:5), and He blamed them for combining such outward scrupulosity with blindness toward the inner state of the soul. Like the hypocrites they were, they were careful to cleanse the outside of the cup and the plate, while inside their souls were full of extortion and greed (Matt 23:25).

In contrast to this disparity between outer ritual cleanness and inner spiritual filth, Christ focused entirely upon the inner state. It was the clean of heart who would see God and be able to truly approach him in worship. Approaching him in a state of ritual cleanness while one’s heart was unclean was useless and worse than useless. If one cleansed one’s heart of stain, one could confidently approach God. Indeed, the sight of him was guaranteed.

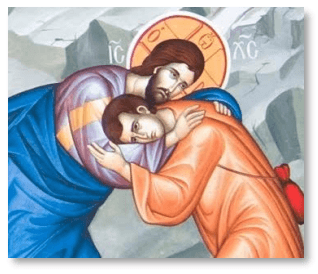

In these Beatitudes, Christ also commended the peacemaker. In our modern culture,  the idea of a peacemaker inevitably conjures up pictures of a third-party diplomat trying to reconcile warring groups. But that is not the picture that would have been imagined by our Lord’s original hearers in the first century. In that day, the peacemaker pictured by our Lord was the aggrieved party who strove for peace and forgiveness rather than for retaliation for wrongs suffered and justice that was owed. Third party diplomats were few and far between; most quarrels involved only two combatants.

the idea of a peacemaker inevitably conjures up pictures of a third-party diplomat trying to reconcile warring groups. But that is not the picture that would have been imagined by our Lord’s original hearers in the first century. In that day, the peacemaker pictured by our Lord was the aggrieved party who strove for peace and forgiveness rather than for retaliation for wrongs suffered and justice that was owed. Third party diplomats were few and far between; most quarrels involved only two combatants.

Making peace therefore involved offering forgiveness—or at least shelving the justice owed to wrongs suffered. The peacemaker of this Beatitude was the suffering party in a quarrel who refused to prolong the quarrel, and who preferred peace and reconciliation to justice. In a world in which forgiveness was rarely considered, such an irenic and forgiving spirit was hardly ever seen. In most quarrels and wars, the victorious crushed their foe and pressed their advantage; the vanquished pulled from the wreck whatever they could and hoped that the day would come when they could take their revenge. In this Beatitude, Christ undercuts such miserable moral mathematics and such dubious diplomacy, and bids both parties of the quarrel to stand down.

Christ also commends his disciples when they were persecuted for righteousness’ sake. This Beatitude overflows into the next one: “Blessed are you when men revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely for My sake. Rejoice and be glad, for great is your reward in heaven.” The term righteousness is a kind of theological code for God’s work through Jesus of Nazareth. The term righteousness denotes God’s faithfulness to his covenant promises, his reliable fulfilling of what He had said through his prophets that He would do to restore his people. Christians believe that God fulfilled his prophetic promises through the life and work of Jesus the Messiah, so that through him God fulfilled all righteousness and kept his promises to his people. Therefore, those who were persecuted for righteousness’ sake were those who were persecuted for their faith and discipleship to Jesus. Living eschatologically and with a different spirit than everyone else lives will inevitably bring down upon oneself hostility and persecution. Christ bids his disciples to be strong, to be calm, and to carry on.

Read more: The Beatitudes (opens in a new tab)