The Relics of the Saints

It is safe to say that the secular world which sometimes appreciates the Church’s icons has little appreciation for its relics. Relics seem to form the line in the sand, separating those animated by the spirit of the age from those animated by the tradition of the Church.

Antipathy to relics goes back a long way. The “Thirty-nine Articles” of the Church of England at the time of the Reformation declared, “The Romish Doctrine concerning…Worshipping and Adoration, as well of Images as of Reliques, and also invocation of Saints, is a fond thing vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture, but rather repugnant to the Word of God.”1 The Anglican Divines were of course reacting to medieval Catholicism, but it is doubtful that their attitude to the modern Orthodox Doctrine concerning the adoration of images and relics would have been much different.

Those Protestants were not the only ones who found the veneration of relics repugnant. This was the universal view of the ancients as well. Pagan Romans as well as Jews regarded contact with the bones of the dead as defiling, and as bringing ritual contamination. Touching a corpse or the bones of the dead rendered the person ritually unclean and so temporarily unable to offer sacrifice or to take part in a religious rite. That is why they took care to bury their dead outside the city, where the possibility of such ritual contamination was minimized. This was not simply a theological opinion, but a deeply felt visceral reaction.

This tradition reveals the great abyss separating paganism from early Christianity. The pagans (and Jews) took great care to avoid contact with the remains of the dead. Christians took great care to collect and treasure the bones of its saints. Indeed, the bones and remains of the martyrs were not regarded as defiling, but as sanctifying. That is why the Christians would keep the feast of their martyrs over their very bones, for they felt that such contact brought the blessing of God. Even today, every Liturgy is served over the bones of the martyrs, for a tiny fragment of their relics is sewn into the back of the antimension over which the Liturgy is celebrated.2

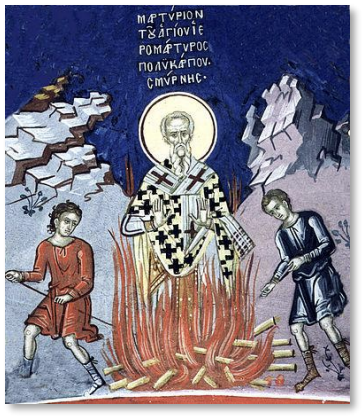

This love for the relics of the saints began quite early and has a stronger history even than that of iconography. Thus in 155 A.D., the Christians were keen to collect the relics of the newly martyred bishop Polycarp so that they might venerate them. In the story of his martyrdom we read,

Later on [after the cremation of Polycarp’s body by the Romans] we took up his bones, which are more valuable than precious stones and finer than refined gold and deposited them in a suitable place. There, when we gather together as we are able, with joy and gladness, the Lord will permit us to celebrate the birthday of his martyrdom in commemoration of those who have already fought in the contest, and also for the training and preparation of those who will do so in the future.3

From this we see that already in the mid-second century the Church had a firm tradition of venerating the relics of its saints. As the author of the Martyrdom of Polycarp wrote, this love for the martyrs offered no rival to their love for Christ, “for we worship this One who is the Son of God, but the martyrs we love as disciples and imitators of the Lord, as they deserve, on account of their matchless devotion to their own King and Teacher.”4

The principle behind the Church’s veneration of relics undergirds all of its sacramental theology. That is to say, by the power of the Spirit of God, matter can become spiritbearing. This principle was foreshadowed in the Old Testament, when the bones of Elisha brought life to someone who had recently died (2 Kings 13:20–21). It is seen more fully in the New Testament, when even handkerchiefs and aprons which had touched the body of St. Paul became charged with divine power so that the sick were healed and demons were cast out (Acts 19:11,12). If mere cloths which had come into contact with St. Paul could become vehicles of healing, how much more the body of the apostle himself!

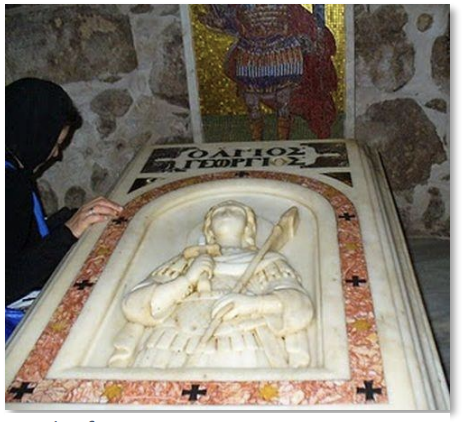

Relics of the saints were not as plentiful as their icons, for obvious reasons. The early church had a reluctance to divide up the bones of the dead but wanted to keep the body of the departed saint whole—as an Empress discovered to her disappointment when she asked the bishop of Rome for a fragment of the relics of Peter. The bishop of Rome declined, saying that it was “not their custom.” But demand for relics grew, and eventually the Church overcame the Roman reluctance to divide the bones of its saints. Today’s relics are usually a small fragment of the saint’s bones, preserved with honor in a reliquary, a little chest set out for veneration at certain times. These relics are considered to be sources of blessing. Sometimes the faithful find miraculous healing from venerating them, as they ask for the prayers of the saint.

Encountering a relic means encountering the saint himself, who by the grace of God is not separated from his relics. The Church’s understanding of the union of the saint with his relics reveals the abyss separating the Church from the modern secular world. In the secular realm, a body has no significance after death. Often it is cremated, and not even present at the funeral of the deceased. Like the pagans of old, modern secularists regard the immaterial soul as alone possessing true personhood. After death, the body is discarded as easily as one discards an envelope after taking the letter enclosed in it. The envelope (or the body) is not longer of any use; only the letter (or the soul) matters.

This is contrary to the thought of both the Old and New Testaments. The human person consists of an amalgam of body and soul, which together constitute the human person. The body does not lose its personhood after death—which is why the soul of the saint still recognizes his own body5 and has a connection with it. That is also why those coming to visit the relics of Peter in Rome in the early church did not say that they were visiting his relics but visiting Peter.

The Church’s use of relics witnesses to its eschatological nature, which is also revealed through its most honoured members, the martyrs. The saints live by the power of Christ’s Resurrection, and in some measure already partake of the age to come. The powers of that age already seep into this age through the heroism of the martyrs and remain among us through their relics. The relics witness to the truth that death is not the end. Death has been changed by Christ, and made a doorway into life, sanctification, and joy.

Footnotes

-

3 Article XXII. By “fond” was meant “foolish.” ↩

-

The antimension is the cloth spread out on the altar table before the Gifts of bread and wine are placed upon it and the Eucharist itself is celebrated there. ↩

-

The Martyrdom of Polycarp, chapter 18. ↩

-

The Martyrdom of Polycarp, chapter 17 ↩

-

Thus St. Gregory of Nyssa, in his work On the Soul and the Resurrection. ↩