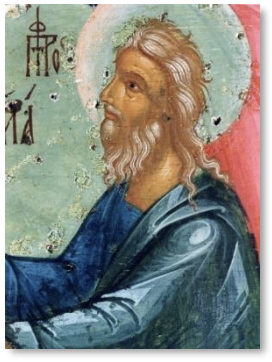

The Father

The Primacy of the Father

For the Orthodox, discussion of the Holy Trinity must begin with the Father. He is the principle of unity within the Trinity: the Son is divine because He is the Son of the Father, eternally begotten by him; the Holy Spirit is divine because He is the Spirit of the Father, eternally proceeding from the Father and resting in the Father’s Son. Though Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are all co-equal and co-eternal, the Father is the aitia, the cause of the Son and the Spirit, not in terms of time (as if the Son and Spirit came into being after the Father), but hypostatically, in terms of their personhood. The fathers referred to this as “the monarchy” of the Father.

We see this primacy of the Father asserted in the creed. The Nicene Creed begins by declaring, “I believe in one God, the Father Almighty.” That is, there is only God—viz. the Father almighty. But the Father is not alone. He has with him his only-begotten Son and Word, begotten of the Father before all ages, homoousios1 with the Father, sharing his ousia, his essential divinity. Also, the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father—i.e., He was not created by him as were the angels but has his hypostatic existence from the Father’s own being. Thus, the Creed proclaims the Trinitarian nature of God, while asserting the hypostatic primacy of the Father.

The Father may also be identified with the God of the Old Testament, the One worshipped by Israel (The Creed also hints at this when it declares that the Father is the “Maker of heaven and earth”). The God of Israel, worshipped by them under the names of Yahweh2 and Elohim, had his “house” or temple in Jerusalem. This temple was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 B.C. but rebuilt after the exile and enlarged later still by Herod the Great. This temple was still the Temple of Yahweh. Jesus referred to it as “my Father’s house” (Luke 2:49). The Temple of Yahweh was the Temple of Jesus’ Father. The Father, therefore, was Yahweh, the God of the Old Testament.

The Self-Revelation of Yahweh in the Old Testament

Since the days of Marcion in the second century, it has been common for some people to contrast the God of the Old Testament with the God of the New Testament, to the disadvantage of the former. These people assert that Yahweh, the God of the Old Testament, was angry, vindictive, and warlike, while the Father, the God of the New Testament, is kind, patient, forgiving, and loving. Marcion drew the obvious conclusion from this dubious comparison and asserted that the Father was not the God of the Old Testament, and that Christ came to reveal an entirely different deity from the angry God known to Israel.

The Church quickly disowned Marcion and asserted that the God known in the Old Testament was indeed the Father revealed by Christ. Yet even with this denial, some Christians still cling to the caricature of the Old Testament God as one of wrath and angry intransigence, compared to the loving God of the New Testament. It is therefore important to examine the portrayal of Yahweh Elohim in the Old Testament. When we do so we shall see that his character is precisely that of the Father, and of Jesus, the Father’s Son.

The Old Testament begins with a series of stories ascribing the creation of the world and all the world’s people to Yahweh, the tribal God of Israel. The other creator gods of the pagan nations are entirely side-lined, discounted, and cast out of the narrative, deprived of their divine status by being ignored by the biblical narrator, their claims to creating and governing the world being disallowed. Yahweh alone is the creator and sustainer of the world, the One who cares for all that He has made.

Thus, Yahweh is first revealed as having a caring relationship with everyone in the world, even though they were not part of his chosen covenant people. St. Paul would later stress this, by declaring to the Lycaonians, “In past generations [the living God] allowed all nations to walk in their own ways, yet He did not leave Himself without witness, for He did good and gave you from heaven rains and fruitful seasons, satisfying your hearts with good and gladness” (Acts 14:16–18). God’s self-revelation to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob did not erase or supplant his care and solicitude for all men.

When God did later reveal Himself to Moses and call his chosen people out of Egypt to enter into covenant with them and fulfil his promise to give them the land promised to Abraham, He revealed even more of his heart through the Law that He gave them. For the Torah given at Sinai was not simply a collection of legislation; it was a manifestation of the divine character. God was holy, and He expected his people to be holy also and strive to imitate him in their daily lives (Lev 11:44–45).

Divine Holiness

What was this divine holiness that the people were called to imitate? Here we focus upon four things: God’s concern for the poor and oppressed; his righteous anger at sin and at oppression; his patience and compassion; his concern for the whole world.

Yahweh’s concern for the poor is expressed in many passages—a concern which shines all the more brightly, given how the plight of the poor was largely ignored in the ancient world and poor people treated like mere human ballast. In contrast, Yahweh commanded his people not to take full benefit from the fields they worked, but to use them to help the poor. Thus Leviticus 19:9 reads, “When you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap your field to its very border, neither shall you gather the gleanings after your harvest. You shall leave them for the poor and for the sojourner.” We also find a similar order in Leviticus 25:35 which reads, “If your brother becomes poor and cannot maintain himself with you, you shall maintain him. Take no interest from him or increase but fear your God that your brother may live beside you.”

This concern for the poor extended even to concern for the preservation of their dignity. In Deuteronomy 24:10–11 we find this command, “When you make your neighbour a loan of any sort, you shall not go into his house to fetch his pledge. You shall stand outside and the man to whom you make the loan shall bring the pledge out to you.”

This concern for the weak even extended to animals. In Deuteronomy 22:6–7 we read,

If you happen to come upon a bird’s nest along the way, in any tree or on the ground, with young ones or eggs in it, and the mother sitting on the young or on the eggs, you shall not take the mother with the young; you shall certainly let the mother go, but the young you may take for yourself, in order that it may go well for you and that you may prolong your days.

This is of a piece with Yahweh’s concern for oxen in Deuteronomy 25:4 where He commands that they be allowed to eat while working at threshing, and not go hungry.

More than this, Yahweh shows his concern even for inanimate flora. In Deuteronomy 20:19–20 Yahweh forbids use of a scorched earth policy in warfare. “When you lay siege to a city for a long time, fighting against it to capture it, do not destroy its trees by putting an ax to them. Do not cut them down. Are trees of the field people, that you should besiege them?” While some may detect an economic motive for preserving birds and trees, the compassion of God for all his creation cannot be excluded.

Yahweh’s righteous anger at sin and oppression is a direct fruit of his compassion for the poor and the helpless. The rich and powerful, then as now, ground the face of the poor, despoiled and murdered them, leaving orphans and widows in their wake in a long trail of destruction, and it was Yahweh’s love for the orphans and widows that provoked his wrath against their oppressors. We see this righteous anger especially in the words of the prophets.

Thus, Amos thunders against the rich with Yahweh’s voice,

For three transgressions of Israel, and for four, I will not revoke the punishment, because they sell the righteous for silver, and the needy for a pair of shoes—they that trample the head of the poor into the dust of the earth and turn aside the way of the afflicted… Behold, I will press you down in your place, as a cart full of sheaves presses down. Flight shall perish from the swift, and the strong shall not retain his strength, nor shall the mighty save his life (Amos 2:6–7, 13– 14).

Here Yahweh shows Himself a protector of the poor, and a mighty avenger of those who destroy them.

Yahweh’s patience and compassion are seen time and time again through the Hebrew Scriptures. His patience with Israel in the wilderness when they openly repudiated and defied him by worshipping the golden calf at Sinai was so proverbial that it was memorialized in psalms such as Psalm 78 and Psalm 106. Even later when they inherited the Land and turned to idols, God was patient, warning them over and over through the prophets to turn back and save their lives.

Yahweh’s heartbreak is seen in such passages of Isaiah 5:1–4, the Song of the Vineyard:

Let me sing for my beloved a love song concerning his vineyard: my beloved had a vineyard on a very fertile hill. He dug it and cleared it of stones and planted it with choice vines; he built a watchtower in the midst of it and hewed out a wine vat in it; and he looked for it to yield grapes, but it yielded wild grapes. And now, O inhabitants of Jerusalem and men of Judah, judge, I pray you, between me and my vineyard. What more was there to do for my vineyard, that I have not done in it? When I looked for it to yield grapes, why did it yield wild grapes?

Yahweh’s frustration can be clearly seen here, especially in the almost pathetic cry, “What more was there to do that I have not done?” He had lavished every care to provide and protect his people and wanted only the fruits of righteousness and devotion in return. But they refused, producing injustice and turning from him to other gods. This went on for centuries, as God continued to wait for their repentance before finally sending judgment. And even then, He judged only with pain and reluctance. As He said through Ezekiel, “As I live, I have no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but that the wicked turn from his way and live! Turn back, turn back from your evil ways, for why will you die, O house of Israel? (Ezek 33:11).

Yahweh’s concern for the whole world is also revealed in the Hebrew Scriptures. It is glimpsed faintly in passages such as Amos 9:7, which speaks of Yahweh’s guiding other nations as He guided Israel. “Did I not bring up Israel from the land of Egypt, and the Philistines from Caphtor and the Syrians from Kir?” But it is found in unmistakably loud tones in the Book of Jonah.

The story of Jonah’s adventures is told for the sole purpose of enlarging the hearts of his people to include the Gentiles—a very tall order in post-exilic Israel, when Israel was suffering under a foreign yoke. The story recounts how Jonah was sent to announce Yahweh’s imminent judgment on Nineveh, and how the Ninevites repented after Jonah proclaimed their doom.

Nineveh was the capital of the brutal Assyrian Empire, known for its ruthlessness and cruelty. Nineveh’s fall was announced by the prophet Nahum, who ended his prophetic diatribe with the rhetorical question to Nineveh, “Upon whom has not come your unceasing evil?” In the story of Jonah, however, Nineveh repented and was not destroyed—much to the distress of Jonah, who feared all along that they might repent and escape justice.

Yahweh gently rebukes Jonah for his hard heart and his determination to see the godless Gentiles destroyed. After causing a plant to miraculously spring up to provide needed shade and then suddenly causing it to die, He asked Jonah if he was angry that the plant died. When Jonah replied in the emphatic affirmative, (“angry enough to die!”), Yahweh retorted as follows,

You pity the plant, for which you did not labour, nor did you make it grow, which came into being in a night, and perished in a night. And should not I pity Nineveh, that great city, in which there are more than a hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not know their right hand from their left, and also much cattle? (Jonah 4:9-11)

In other words, Yahweh has pity upon all the peoples of the world—even upon ruthless and terrible Nineveh.

This is the character of Yahweh, revealed in the Old Testament—kind, just, patient, and compassionate. It is the character of the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, equally revealed in the New. And this was the character of Jesus, for to see Jesus was to see his Father also (John 14:9).

Footnotes

-

Of the same (homo ὁμο) essence (ousia ούσια). ↩

-

The name "Yahweh" is used by some to represent the Hebrew Tetragrammaton (meaning four letters) יהוה (Yod Heh Vav Heh). It was considered blasphemous to utter the name of God; therefore, it was only written and never spoken, resulting in the loss of the original pronunciation. It is more common in English-language bibles to represent the Tetragrammaton with the term "LORD" (capitalized). ↩