Prayers for the Departed

Because the Church is one Body, encompassing both the living and the departed, it is important to consider exactly how we pray for the departed. What is it that they need? For what do we ask? A very clear example is offered by the priest in our services for the departed:

O God of spirits and of all flesh, Who has trampled down death by death, and overthrown the devil, and given life to Your world: O Lord, give rest to the souls of Your departed servants N. (N.), in a place of light, a place of refreshment, a place of repose, where all sickness, sorrow and sighing have fled away. Pardon every sin committed by them in word, deed, or thought, in that You are a good God, and the Lover of mankind; for there is no man that lives and does not sin, for You alone are without sin, Your righteousness is an everlasting righteousness, and Your word is truth.1

This prayer states that God gives to the departed what he has promised in Scripture: to “wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning, nor crying, nor pain anymore, for the former things have passed away” (Rev 21:4).

Additionally, it is a prayer for their sins to be forgiven, with the reminder that there is no one who lives without sin, and that all of us stand in need of God’s forgiveness.

No doubt, such prayers raise questions in the minds of many. Some might hear these prayers as though we were asking God to forgive someone who has not themselves repented. The Orthodox faith has never spoken definitively in such matters, preferring to let the words speak for themselves. There is not a doctrine of purgatory in the Orthodox faith, nor an explanation of the “mechanics” of life after death. There are, indeed, stories and private revelations about these matters shared by various saints, none of which rise to the level of Church dogma. Instead, there is an abiding confidence in the goodness of God towards every creature, and the cry of our hearts on behalf of those we love.

A holy monk once suggested that the life of any individual here on earth affects the lives of those around them. The prayers for such an individual after his death, by those who knew him or were touched by him, are in effect, an echo of his own life, its sound continuing to reverberate in the hearts of others. Our prayers are therefore his prayers as well.

On a psychological level, prayers for the departed offer a very profound means of therapy and healing in the grief of those who have been left behind. They serve as an ongoing communion, reminding us that death does not destroy our relationships. This reality is reflected in the Orthodox custom of offering prayers for the departed on the anniversary of their death. The parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19–31), told by Christ, offers interesting details in this regard:

There was a certain rich man who was clothed in purple and fine linen and fared sumptuously every day. But there was a certain beggar named Lazarus, full of sores, who was laid at his gate, desiring to be fed with the crumbs which fell from the rich man’s table. Moreover, the dogs came and licked his sores.

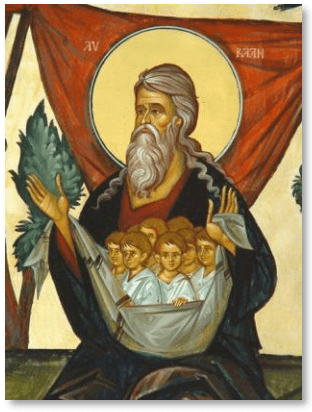

So it was that the beggar died and was carried by the angels to Abraham’s bosom. The rich man also died and was buried. And being in torments in Hades, he lifted up his eyes and saw Abraham afar off, and Lazarus in his bosom. Then he cried and said, ‘Father Abraham, have mercy on me, and send Lazarus that he may dip the tip of his finger in water and cool my tongue; for I am tormented in this flame.’

But Abraham said, ‘Son, remember that in your lifetime, you received your good things, and likewise Lazarus evil things; but now he is comforted, and you are tormented. And besides all this, between us and you there is a great gulf fixed, so that those who want to pass from here to you cannot, nor can those from there pass to us.’ Then he said, ‘I beg you therefore, father, that you would send him to my father’s house, for I have five brothers, that he may testify to them, lest they also come to this place of torment.’

Abraham said to him, ‘They have Moses and the prophets; let them hear them.’ And he said, ‘No, Father Abraham; but if one goes to them from the dead, they will repent.’ But he said to him, ‘If they do not hear Moses and the prophets, neither will they be persuaded though one rise from the dead.’ (Luke 16:19–31)

First, salvation is described as “Abraham’s Bosom,” an image that suggests the uninterrupted communion with the community of faith as a key element of paradise. The Rich Man, however, finds himself cut off and in the torments of Hades. From there, he calls out to “Father Abraham,” as a prayer to a departed saint. Of course, his prayer is rebuffed, and it is explained that help cannot be sent to him. The parable itself is not a story intended to relay details about life after death. It is, however, a story that points towards the importance of care for the poor. But the details of Jesus’ story, paradise being Abraham’s Bosom and the prayer to a saint, draw no notice and receive no rebuke in the gospel. They seem to be details that would have been a normal part of Jewish understanding at the time. Subsequent study has indeed confirmed that the Bosom of Abraham was already a part of Jewish understanding, and that Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, interceded for those who were tormented in the fires of Hades.2

The debates beginning in the 16th century between early Protestants and Roman Catholics resulted in both a refinement and hardening of doctrinal positions regarding life after death3 and the nature of salvation.4 Orthodox Christianity predates these debates and was never part of them. As such, the Orthodox teaching reflects a much earlier understanding of these matters and may, to some, seem to be less developed. There is, in Orthodox thought, a reluctance to speak with authority about things that have not been given definitive treatment in the Scriptures. What we know and understand in the matter of the departed is an abiding assurance in the goodness of God and His willingness for all to repent and be saved (2 Pet 3:9). The Church’s prayers for the departed holds to this hope and gives voice to it in its remembrance before God.

Footnotes

-

Isabel Florence Hapgood, tr., Service Book of the Holy Orthodox-Catholic Apostolic Church, revised edition (NY: Association Press, 1922), 369. ↩

-

Apocalypse of Zephaniah 11:2–4. ↩

-

For example, whether or not one can pray for the departed and whether purgatory exists. ↩

-

For example, whether one is saved by faith alone and what role, if any, good works play. ↩