The Peace of Constantine

Since it was the emperor’s task as Pontifex Maximus1 to preside over the State’s devoted worship of the gods, it was thought by all the Christians, even apart from the imperially sponsored persecutions, that the office of emperor was incompatible with the practice of the Christian faith, and that a Christian emperor was an impossibility, a contradiction in terms. That is why Constantine appeared to the Christians like a thunderclap coming from a clear and cloudless sky.

Whether converted to Christ earlier in life or shortly before entering Rome in triumph in 312, it soon became clear that Emperor Constantine believed in the Christian God and intended to favour the Church. He confirmed the cessation of persecution and allowed the properties of the Church to be returned. He and his immediate dynasty championed the Christian cause, even calling the bishops to Nicaea to sort out the confusion caused by the teaching of Arius and promising to back the official teaching of the Church with governmental support. With Constantine as emperor, a new day dawned for the Church.

Christians at the time wondered whether their new good fortune wasn’t perhaps too good to last, and with the accession of Julian as emperor, it seemed as if their prosperity under Constantine and his sons was indeed just a passing phase. Emperor Julian detested the Christians and was determined to turn back the cultural clock and restore the unquestioned ascendency of the old pagan religion. His sudden death on the field of battle in 363 after a reign of only twenty months brought his pagan agenda to a decisive end. All subsequent emperors would be Christian.

The Roman empire was now officially under the heavenly protection of Christ, who ruled through the might of his chosen servant, the emperor. As the Church rapidly grew in importance, government involvement in Church affairs also grew apace. The government’s determination to use force to root out heresy and enforce an imperiallybacked Orthodoxy was to have both positive and negative effects—especially when the bishops did not actually profess the Orthodox2 faith.

For good or for ill (or both) the Church would experience government involvement in almost every aspect of its life. The emperor was heavily involved in the selection of bishops. And as government-facilitated wealth poured into the church, bishops became very competitive, with rich and important men jockeying for important episcopal positions and those important bishops striving to gain ever more power and influence. From being the targeted leaders of a hunted and persecuted sect, bishops came to be the controllers of wealth and power. The situation was not conducive to finding the best men as leaders, as the good leaders among the bishops recognized and often lamented.

But for all the drawbacks of official government support, the Church under a cooperative Roman State was able to do much good. In particular, such support helped to facilitate the Church’s aggressive evangelism, and in fulfillment of Old Testament prophecy (Isa 60:1–3), many people came to faith in Christ, abandoning their idols and worshipping the one true God. That included a mission to the northern peoples of the Rus at the end of the tenth century, through the missionary labours of such men as Cyril and Methodius

The Church during these centuries flourished. Great and beautiful cathedrals were built and adorned with icons and mosaics, and there was an explosion of hymnography. The Christians abundantly proved themselves capable of producing a culture and an aesthetic as fine and even finer than pagan Roman aristocrats produced before. Hellenism became Christianized.

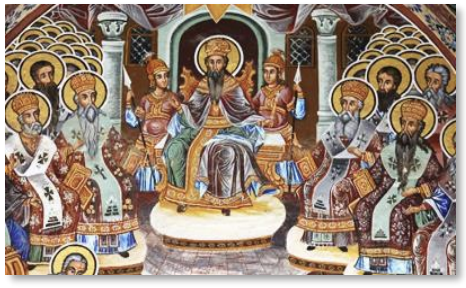

It was during this time that the Church held long and fruitful (and often heated) debates about the exact nature of Christ. Was He truly God in the same sense that the Father was God? Or was He only “like” God? And was He truly as human as we are? And how should one understand the union in him of the divine and the human? These questions were examined and argued over in a series of councils from the fourth to eighth centuries. The councils, whose results were finally accepted by the majority of the Church throughout the world, were called “ecumenical councils”, and these set the standard for doctrinal orthodoxy ever after. The most significant product of the first ecumenical council was the Nicene Creed, which contained the essentials of the Orthodox faith, including the beliefs about God the Father, God the Son, God the Holy Spirit, and the Church. All of the ecumenical councils were held in the east. The results of the councils’ findings had the force of law through imperial support. Dissent from these findings was heresy and was disallowed in a Christian state, wherein the Church and secular worlds had become fused.

These centuries also saw the rise, flourishing, and eventual triumph of monasticism. Thoughtful men and women with money and leisure often went on prayerful retreat in solitude on their properties, removed from the bustle of the town. In the fourth century, beginning most prominently with St. Anthony, Christians in Egypt went further out into the desert, so that the desert became a veritable city, populated by those who sought God in solitude and who pushed the boundaries of their earthly limitations. In places such as Constantinople, urban monasteries arose, where the monastics were very much involved in the society around them, and their contribution to Church life was invaluable. The eastern part of the Roman empire flourished under the cross of Christ.