Holy Orders

One question that may be asked is, “Why does the Church have clergy at all?” Muslims do not have clergy in the same way that Christians do—and neither, if it comes to that, do Quakers. The answer is that the Church is more than a mere collection of assembled Christians. The Church is a body.

St. Paul describes the Church as a body at great length in chapter 12 of his First Letter to the Corinthians. There he writes that just as the different members of a human body have different functions, so the members of the Church as the Body of Christ also have different functions. In the human body, the ear has the function of hearing, the eye, of seeing, the legs and feet, of walking. All these differing functions are necessary for the body to carry out all the different things that it must do. It is the same with the Church—the Church has many functions and tasks it must fulfill to bring all of its members to spiritual maturity.

Because of this, Christ bestows gifts on His Church to help it do the things it must do, giving to some the gift of apostleship, to others the gift of prophecy, to others the gift of evangelism, and to still others the gift of shepherding and teaching (Eph 4:11). These ministries are not ends in themselves—still less were they instituted for the personal benefit of the ministers. Rather, they all serve the common goal of “equipping the saints for the work of service, to the building up of the body of Christ until we all attain to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to mature manhood, to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ” (Eph 4:12–13). That is, all the ministries of the Church, from the highest to the lowest, from that of apostle all the way on down, exist for no other purpose than to help all the laity grow up and mature in Christ. The clergy exist for the laity. That is why clericalism is not only pathological, but also selfcontradictory.

Certain of these ministries are obvious in their function—readers are set apart to read liturgically, and subdeacons are set apart to help the deacons in the service at the altar. Their function is more specific and limited than those of deacon, presbyter, and bishop, and is confined to the liturgical services themselves. It is otherwise with deacons, presbyters, and bishops, for they continue to exercise their ministry even after the liturgical services have ended. They have a pastoral responsibility in that they work intimately with the people. For this reason, they have a greater accountability and are set apart with more solemn prayer. That is why the Church exercises more care in choosing deacons than in choosing subdeacons. In the present rites of ordination, deacons, presbyters, and bishops are hailed with the cry of Axios! Worthy! because their suitability for their ministry is of the utmost importance to the health of the Church.

What are the functions of those ministries ordained by solemn laying on of hands? Let us look at them one by one. Deacons are the institutional servants of the Church, responsible for the exercise of the congregation’s diakonia. Indeed, the word “deacon” means “servant,” and diakonia means “service”. Presbyters are the Church’s rulers and counselors. The term “presbyter” comes from the Greek presbyteros, meaning “elder,” or “old man”, and in Israel it was the elders who ruled the local communities.

In the early church, each congregation had several presbyters who formed a council around the leading presbyter, the bishop. The bishop was the main liturgist who presided at the services, surrounded by his fellow-elders. They were the ones who made the pastoral decisions and ruled the local church under the guidance and vision of the bishop.

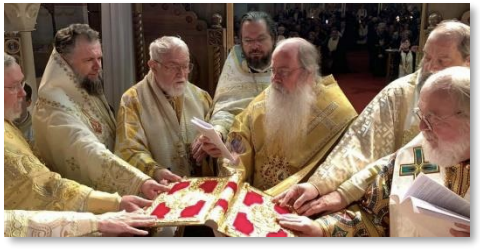

Bishops are the Church’s main celebrants and teachers. In the early church, a bishop served as main pastor and liturgist of every local congregation. He was the one who offered the prayers at the weekly Eucharist, baptized the new converts, anointed the sick, and restored the excommunicated penitent back to the Church. He was the one who gave the sermon each Sunday, and it was his orthodoxy (or lack of it) which determined whether his congregation was recognized as orthodox by the rest of the church. His most important task, therefore, was to preach the Gospel, to “rightly define the word of truth.” This concern for the orthodoxy of each bishop is the reason why he is thoroughly examined prior to his ordination as bishop in our modern rites.

This concern for the orthodoxy of each bishop is the reason why he is thoroughly examined prior to his ordination as bishop in our modern rites.

Holy Orders are therefore Christ’s gifts to the Church, as each of these functions is a charisma or spiritual gift. But as important as they are, they are not the totality of the Church, and they exist only to serve the laity. Indeed, in one sense the clergy are a part of the laity, in that they all form part of the holy laos, the people of God. Therefore, we see them standing in the church, the clergy and laity alike, facing the same way when they pray. All face east. All face the same Lord, receive the same salvation, and are called into the same Kingdom.