A Kingdom of Priests

The book of Exodus is the story of God creating a kingdom of priests (Ex 19:6). In line with the promise to Abraham, Israel must be brought out of the slavery of Egypt and led back to the promised land. They will not only accomplish this in a physical journey and conquest, but they will be shaped into a holy nation, a nation of priests, who will be able to speak and prophetically witness to the truth of God throughout the world. How will God accomplish this forging of a nation of priests?

The center of Exodus does not lie in the miracles of God wrought over the idolatrous Egyptians—though, it should be noted that the plagues are obvious echoes of the creation account in Genesis. The idolaters are the ones for whom creation rejects and overwhelms. Rather, the core of Exodus is the revelation of God to Moses and Israel on Mount Sinai. There God reveals the ways in which he will form his kingdom of priests. He will accomplish this through his Law, which instructs Israel in holiness, and through his tabernacle, where he will reshape the heart of Israel through worship.

The encounter with God on Mount Sinai is shot through with the Temple themes we saw in Eden. God dwells within his Temple wrapped in smoke and fire, signs of his power, holiness, and a lack of easy accessibility.1 God no longer walks in the garden with his perfect creation; rather He must teach and perfect mankind through his holy, but mediated, presence and guidance. As He had led Israel out of Egypt by a pillar of smoke and a pillar of fire, so as they approached Mount Sinai there was the presence of smoke and fire, signifying the presence of God (Ex 19:16–19, 24:15–18). God warns Israel that there are specific boundaries on this mountain in that only certain people will be allowed access to the top of the mountain. There is a three-part gradation of holy space.2 All people may come to the foot of the mountain and see the fire and smoke. Aaron, his two sons, and seventy elders are allowed part way up the mountain for a meal with God. Finally, only Moses was brought into the most intimate of places. The nearer one drew to God, the more intense was the holiness and stringent the requirements of access. This three-part access is repeated in the later tabernacle and Temple. The courtyard is open to all Israel. The first room of the Temple was open to Levitical priests. And, finally, the holy of holies, was only accessed by the high priest. The rupture of communion requires a pedagogy and therapy of appropriate boundaries. Humanity cannot waltz into the presence of God but must approach God in the ways appropriate to their relationship.

On Mount Sinai, Moses is given the Law and the instructions for building the tabernacle (Ex 25–31). The instructions for building the tabernacle echo in very specific ways the creation account in early Genesis. There is the repetition of “then the Lord said” echoing “and God said”, the mention of gold, precious jewels (like onyx), and cherubim and, finally, the final instruction given to Moses is an echo of the final act of God in creation, God reminds Moses to keep the sabbath day of rest. Aspects of Eden are being restored.

What stood at the center of the holy of holies? The ark of the covenant. God commands Moses to build a gold box which will reside within the holy of holies. Within the ark will lie the Ten Commandments, the ten guiding points of God’s Law—a general summary of the beliefs and ethos of Israel (Ex 25:10–26). Alongside the Ten Commandments lie a jar of manna (Ex 16), Aaron’s staff (Num 17), and later, the teachings of Moses (Deut 31). The entire covenant of Israel can be summed up within the ten commandments. First, the correct relationship to God is paramount—worshiping the creator rather than the creature. From this correct worship flows the ethics of Israel. It is upon the two tablets of stone that God writes his Law in order for his priest kings to rightly teach the commands of God. Enshrined at the very heart of Israel’s worship is the correct understanding of God, creation, and mankind, which is a step toward remedying the falsehood brought into the garden. God’s pastoral care for Israel is underlined by the presence of the jar, staff, and more teachings of Moses. It is of course completely in character for Israel in the midst of this revelation, at the very foot of the mountain of fire and smoke, for them to grow lax and turn to idolatry. And the route they take is to turn to Aaron, the future high priest of Israel, to make a golden calf and an altar and to worship it as the one who saved them from Egypt—yet another example of the constant temptation to turn to the creature rather than the creator. Moses, as their leader, corrects them and then turns back up the mountain towards God in order to make atonement, to mediate and intercede for the sinful damage wrought by the Israelites.

lie a jar of manna (Ex 16), Aaron’s staff (Num 17), and later, the teachings of Moses (Deut 31). The entire covenant of Israel can be summed up within the ten commandments. First, the correct relationship to God is paramount—worshiping the creator rather than the creature. From this correct worship flows the ethics of Israel. It is upon the two tablets of stone that God writes his Law in order for his priest kings to rightly teach the commands of God. Enshrined at the very heart of Israel’s worship is the correct understanding of God, creation, and mankind, which is a step toward remedying the falsehood brought into the garden. God’s pastoral care for Israel is underlined by the presence of the jar, staff, and more teachings of Moses. It is of course completely in character for Israel in the midst of this revelation, at the very foot of the mountain of fire and smoke, for them to grow lax and turn to idolatry. And the route they take is to turn to Aaron, the future high priest of Israel, to make a golden calf and an altar and to worship it as the one who saved them from Egypt—yet another example of the constant temptation to turn to the creature rather than the creator. Moses, as their leader, corrects them and then turns back up the mountain towards God in order to make atonement, to mediate and intercede for the sinful damage wrought by the Israelites.

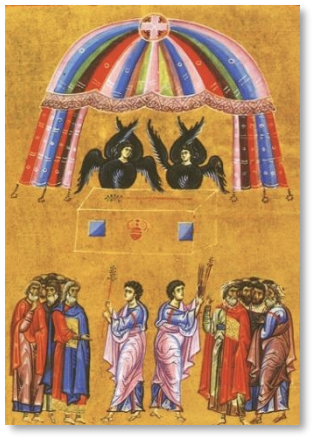

The need for reconciliation, or atonement, between God and Israel is also at the heart of the Temple. The cover of the ark was called an “atonement cover” which held two golden cherubim with wings overshadowing the cover (Ex 25:17–22).Here God tells Moses, “…above the cover between the two cherubim that are over the ark of the covenant law, I will meet you and give you all my commands for the Israelites.” These two cherubim again underline the holiness of God. They guard Eden as they guard the presence of God. Angelic attendants, called seraphim, will later attend the theophanies of God. “The Lord reigns, let the nations tremble; he sits enthroned between the cherubim (Psalm 98 [99]:1).” From the ark of the covenant God reigns. The throne of God is upheld by the golden footstool, the ark of the covenant.

We must more fully develop the “atonement cover." Once a year, on the Day of Atonement, the high priest would enter the holy of holiest and smear blood on the “atonement cover.”3 On the footstool of God, between the cherubim, and above the Law of God, blood is smeared to cover the failure of Israel to live up to its Adamic vocation. The loss of Eden by Adam and Eve is slowly being restored via the condescension of God to mankind to bring them back into communion with himself. This will be continued in the Temple of Jerusalem once the promised land is won from the various tribes and within the possession of the kings of Israel.

We would be remiss in not mentioning many other aspects of the tabernacle and later Temple. The table with the bread of presence, upon which lie golden plates, and from which the priests eat the bread set there, perhaps an echo of Aaron and the elder’s meal on Mount Sinai.4 Or, the golden lampstand, a tree-like oil lampstand which echoes the tree within the garden and also the burning bush from which God called and set aside Moses for his ministry.5 Worship within the holy space of Israel, whether within the tabernacle or within the Temple, was accompanied by sacrifice, incense, the presence of angelic beings—even being woven into the curtains, which should be certain colors, gold, and precious jewels. The end of this worship, an echo of the paradise of communion with God, was to reform the hearts of Israel and to begin to outline for them the contours of edenic living. It is important to underline the emphatic message of God to Moses—that the worship of Israel was to be according to the pattern shown to Moses. The failure to worship God correctly was to corrupt the pattern and to worship God according to the dictates of humanity. Again, a repeat and echo of the age-old problem. Does one follow the way things have been made and dictated by God? Or, do we pursue our own goals and goods?

The end of Exodus outlines the construction of the tabernacle and the final resting of God with the descent and filling of the tabernacle with the glory of God. God has returned to his rightful throne among his people. Will Israel stick to the Law of God? Will she worship Him in holiness and in the pattern revealed to Moses? Will she speak truthfully and fully of the commands of God? Or, will she fail in her vocation to be a light to the world, the elect people of God, a kingdom of priests?

Read more: Priesthood (opens in a new tab), Law (opens in a new tab), Altar Table, Oblation Table (opens in a new tab) Holiness (opens in a new tab)

Footnotes

-

These themes will attend almost every later theophany of God, e.g., Isaiah 6. ↩

-

J. Daniel Hays, The Temple and the Tabernacle: A Study of God’s Dwelling Places from Genesis to Revelation (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books 2016), 34–35. ↩

-

Hays, The Temple and the Tabernacle, 40; Leviticus 16. ↩

-

Hays, The Temple and the Tabernacle, 43–44. ↩

-

Hays, The Temple and the Tabernacle, 44–48. ↩