Miracles, Healings and Exorcisms

The miracles of Jesus have been, of course, a source of contention since the time of the Enlightenment. The newfound loyalty to the scientific method more and more entailed a skepticism regarding God circumventing the normal sequence of events or chain of causation, leading more and more people from that age on to belittle ancient naiveté. Some who remained attached (at least emotionally) to Christianity discovered inventive ways to retain what they considered a deeper significance to the miracles than their ability to evoke awe and wonder. For example, the miracle of the feeding of the thousands was understood more as a parable of sharing (based on the example of the young boy with his loaves and fishes). In extreme cases (e.g., 19th century philosopher David Strauss), even Jesus’ resurrection was transformed into a parable, or “myth” concerning the renewal of humankind in general. More pragmatic minds concentrated mostly on the teaching of Jesus, and its affirmation of the “brotherhood” of all human beings but left the miracles aside as an expression of the first century mindset that more advanced cultures cannot share. (Recently, in a turn away from modernism, there are those who are more open to unusual events than their Enlightenment-formed forbears. However, the “post-modern” imagination would eschew any Christian claim that these signs point specifically to the Triune God, rather than demonstrating the potential of human beings). For those who recite the creeds, however, it is apparent that God-enacted miracles are part and parcel of the gospel, for we celebrate the creation out of nothing, God becoming human, the resurrection of Jesus, and the working of the Holy Spirit, who gives spiritual gifts to the Church. We confess that this same Spirit is “everywhere present and fills all things”—sometimes acting through the chain of ordinary events, but sometimes in astonishing ways.

Miracles

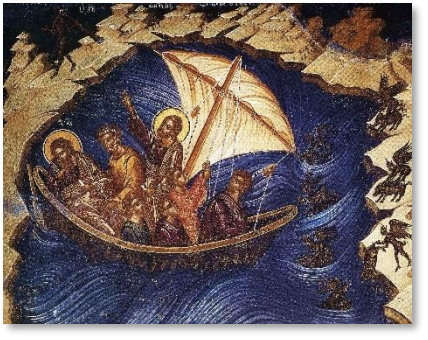

It is helpful for us to consider the different terms used in the Gospels for miracles— mighty acts (Greek, dynameis), signs (semeia), wonders (terata), and “works” (erga). Of these, the word “wonder” most easily captures the sense of our word “miracle,” which comes from the Latin, and means literally, “something to be wondered, or marveled, about.” The paired term “signs and wonders” is found throughout the Old Testament concerning the actions of Almighty God, especially during the time of Pharaoh, and sometimes by the hands of Moses and Aaron. When applied to Jesus’ deeds, the implication is clear that this Man is acting as God in the midst of Israel. John uses both the term “sign” for the miracles that he numbers and also the word “work,” just as he speaks of the Father and Son working in concert (John 5:17): what Jesus performs is an active sign of his identity and harmony with the Father. But the miracles are not only theological signposts. They act mightily among God’s people, as his compassion works for their good. Some of these mighty acts have to do with healing, some with feeding, some with rescuing from the turbulent waves. As we read through the Gospels, we are reminded of the God of Israel and his compassion towards the people, as seen in Psalm 106 (MT 107)—redeeming from trouble, gathering together, feeding them when hungry, bringing the rebellious out of darkness, rescuing from prison, nearing the gates of death in illness, saving them from the tempestuous waves, bringing them to a haven, raising up the needy. All these “works and wonders” of God are replicated in the God-Man, by whom, as with the Psalm, we may “consider the steadfast love of the Lord” (106:43). They show who He is, but also work for our good.

is found throughout the Old Testament concerning the actions of Almighty God, especially during the time of Pharaoh, and sometimes by the hands of Moses and Aaron. When applied to Jesus’ deeds, the implication is clear that this Man is acting as God in the midst of Israel. John uses both the term “sign” for the miracles that he numbers and also the word “work,” just as he speaks of the Father and Son working in concert (John 5:17): what Jesus performs is an active sign of his identity and harmony with the Father. But the miracles are not only theological signposts. They act mightily among God’s people, as his compassion works for their good. Some of these mighty acts have to do with healing, some with feeding, some with rescuing from the turbulent waves. As we read through the Gospels, we are reminded of the God of Israel and his compassion towards the people, as seen in Psalm 106 (MT 107)—redeeming from trouble, gathering together, feeding them when hungry, bringing the rebellious out of darkness, rescuing from prison, nearing the gates of death in illness, saving them from the tempestuous waves, bringing them to a haven, raising up the needy. All these “works and wonders” of God are replicated in the God-Man, by whom, as with the Psalm, we may “consider the steadfast love of the Lord” (106:43). They show who He is, but also work for our good.

Exorcisms

In hearing of Jesus’ healings, his exorcisms of the oppressed and possessed, his compassionate feeding of the crowds, his walking on the water, we may wonder at who He is: miracles lead us to do theology. But they also lead us to gratitude as we consider his great love for us. The way that the Evangelists give shape to these wondrous stories leads us in both directions—to adore God, and to give thanks. The stories witness to his identity, and they also are for our benefit, for as Fr. Alexander Schmemann insists, we are primarily homo adorans (Mankind made to worship).1 God’s identity and his generosity are one, and so each miracle narrative indicates the Gospel in a nutshell, nudging us closer to him, when we respond appropriately.

Footnotes

-

Schmemann, For the Life of the World, 22. ↩