Eucharist

The earliest title of the main Sunday service of the Christian Church is “the Eucharist”, from the Greek word eucharisteo, meaning, “to give thanks.” As early as about the middle of the second century, Justin the Philosopher wrote that the bread and wine which the Christians received sacramentally was “called among us ‘the Eucharist’, “of which no one is allowed to partake but the ones who believe that the things which we teach are true.”1 The ritual service would also later be called “the Divine Liturgy”, and “the Mass”.

The Lord Jesus commanded his disciples to perform this ritual on the night on which He was betrayed. Before noon the next day, He would be crucified and hanging on a Roman cross, offering Himself as a voluntary sacrifice to take away the sins of the world, and within a few hours, He would be dead. He therefore instituted this ritual as the way of ensuring that his sacrifice would be powerfully present and effective among his disciples. By doing so, He transformed what was a simple judicial execution into an enduring sacrifice. The recurring ritual of the Eucharist was the means whereby his disciples could benefit from that sacrifice.

The Lord instituted the Eucharist during his final meal with them. A large, furnished upper room was prepared for Jesus and his disciples to eat their last meal together. At the beginning of this meal, the Lord took bread and broke it. This was not unusual; every meal began with the breaking of bread. But what happened next was unusual—as He gave them the bread, He said, “This is My body which is given for you” (Luke 22:19). The apostles’ reaction is not recorded, but one can imagine their alarm. Then, at the conclusion of the meal, a final cup of wine was blessed and drunk. Again, this was not unusual; every meal would be accompanied by wine, and every Passover meal concluded with this third cup. But as Christ gave them the wine, He said, “This cup is the new covenant in My blood, which is shed for you” (Luke 22:20). As St. Paul recounted it to the Corinthians (in a letter which predated the writing of the gospels), Christ added that they should do this “for My memorial” (sometimes translated “in remembrance of Me;” the Greek is eis tān emān anamnāsin). It is doubtful that the apostles understood what our Lord was talking about, for they had refused to believe that He was about to die. But his words sounded ominous enough. It was only later that they would understand.

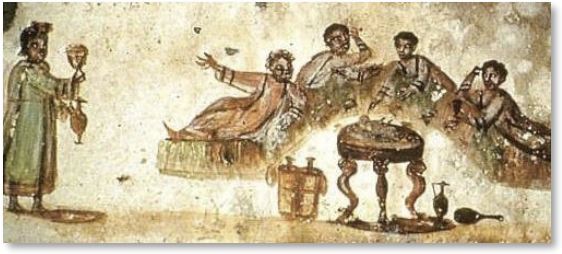

Christ met with his disciples on Sundays after His Resurrection, and by this, He was telling them that the first day of the week was the day when they should come together. Accordingly, though the apostles would continue as good Jews to worship with their fellow Jews in the synagogues on the Sabbath, they would also meet with their fellow Christians on the next day. This day they soon began to call “the Lord’s day”, because it was on this first day of the week that the risen Lord manifested Himself to them when they were together. They would meet every Sunday evening for a meal—a full meal, a supper (Greek deipnon), during which there would be prayers, Scripture readings, hymns, and of course stories about Jesus. The culmination of the meal would be the Eucharist, when the one presiding over the meal would take bread and wine, pray over them, break the bread, and all would eat and drink.

By the end of the first century or the beginning of the second, the taking of the sacramental bread and wine had become separated from the meal itself. The Christians would meet before dawn on Sunday morning (which of course before Constantine’s time was just another workday) and have the Eucharist. They would then gather again later that day for the meal itself, which they called an agape, or “love-feast”. We know this from a letter that Pliny wrote to his emperor, Trajan, in about 112 A.D. He reported that the Christians’ “custom had been to gather before dawn on a fixed day and to sing a hymn to Christ as if to a god…With this complete, it had been their custom to separate, and to meet again to take food—but quite ordinary, harmless food.”2

What was this bit in Pliny’s letter about “ordinary, harmless food?” Here we arrive at the heart of our faith and the central mystery of the Eucharist. Pagans at that time believed that we Christians met together to practice cannibalism, that we killed and ate a baby at our services. And of course, Christians whispered about “receiving the Body and the Blood.” What else could it mean except ritual child-killing and cannibalism? That was why Pliny made a point of reporting that at our meals the food was “ordinary and harmless”—no cannibalism, so far as he could tell.

But if not cannibalism, what does this talk about eating flesh mean? It is a stunning image, and one that goes back to Christ Himself: “He who eats My Flesh (Greek sarx) and drinks My Blood has eternal life…he who eats Me, he also shall live because of Me” (John 6:54, 57). The Lord’s words on the night of his last supper should be understood as a sacramental application of this earlier teaching—when the disciples ate the bread at the Eucharist in the church, they also ate his Body, his Flesh. When they drank the wine, they also drank his Blood. St. Paul taught precisely this: “Is not the cup of blessing which we bless a sharing (Greek koinonia, participation) in the Blood of Christ? Is not the bread which we break a sharing (Greek koinonia) in the Body of Christ?” (1 Cor 10:16). In some sense then, the eucharistic bread was His body, and the wine in the cup was His blood. It was not a simple metaphor (like Christ saying, “I am the vine” in John 15:1). Paul said that what was shared and eaten was His body and His blood. And he said that some of those who ate it improperly had sickened and died as a result (1 Cor 11:30). No one dies from a mere metaphor.

How then could Christ’s Body and Blood be present for us? Because in the Eucharist, the Church obeys Christ in making a memorial (Greek anamnesis; Hebrew zikkaron) of His Passion. Most people today do not understand memory or memorial as the ancient Hebrews did. For us memory is something in our heads, a merely mental activity, like daydreaming. But in the Biblical understanding, a memorial is something done so that God will remember and act. Take, for example, the blowing of the silver trumpets which Moses was commanded to make in Numbers 10:1f. The Hebrews were to blow the trumpets over their sacrifices “that you may be remembered before the Lord your God and be saved” (Num 10:9). The memorial was the act of blowing the trumpets; God remembered and acted. Or take the example of Cornelius the centurion in Acts 10:31. The angel told him that his “alms have been remembered before God.” That is, his alms functioned as a memorial, and God remembered and acted—in this case, the action of sending Peter to him with the Gospel.

It is in this biblical sense that Christ made the eating and drinking his memorial. By eating and drinking at the Eucharist, the Church makes his memorial, and by the power of the Holy Spirit God remembers Christ’s Passion and saves us. In this way, Christ’s Passion is present among us. His death is not merely a past historical event, but a present sacrifice, effective and powerful in our midst. The Sacrifice is present on the Holy Table, and by partaking of the Bread and Cup, we partake of his Body and Blood, his Sacrifice.

The Eucharist is therefore our participation in the saving self-offering of Christ. When we eat his Body and drink his Blood, we receive his divine life and abide in his salvation, receiving forgiveness, healing, transformation, and the power of the Holy Spirit. The Eucharist is thus the fiery center of our Christian life. It is also what binds us together one with another as the Church. Indeed, in the Eucharist, we enter into the fullness of the Church, renewing us and reconstituting us week by week as the Body of Christ. As St. Paul said, “We who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread” (1 Cor 10:17). The Eucharist is thus the source of our common unity in Christ; it is the ecclesial sacrament par excellence. It is not surprising if the Eucharist was liturgical context for all the other sacraments of the Church. Even now, in Orthodoxy, all ordinations are performed at the Eucharist.

As St. Paul said, “We who are many are one body, for we all partake of the one bread” (1 Cor 10:17). The Eucharist is thus the source of our common unity in Christ; it is the ecclesial sacrament par excellence. It is not surprising if the Eucharist was liturgical context for all the other sacraments of the Church. Even now, in Orthodoxy, all ordinations are performed at the Eucharist.

Given the Eucharist’s central place in our salvation, we should prepare ourselves carefully to receive it. We do this by fasting from midnight the night before, so that we come to the Chalice with hungry stomachs and hungry hearts. We do this by praying beforehand that we may receive worthily, forgiving all who have sinned against us and hurt us, and repenting of our own sins. We do this by living all our days in fervent faith, receiving the sacrament of Confession regularly, being faithful in daily prayer and in Scripture-reading, always striving to please the Lord in all things. In other words, we come to the Chalice as Christians, as those who live for the Lord. Thus, every Sunday and every feast-day finds us at the Chalice, partaking of salvation. We come every week because we need to. We come every week because we are unworthy and sick and need to be healed. We come every week because He told us to. We come in the fear of God and with faith and love because without this feast, we have no life.