Man’s Original Vocation

As we carefully read the first chapters of Genesis, we discover that man was entrusted by God with certain duties. As the one called and designated to be God’s image, Adam was to act on God’s behalf as king, priest, and prophet. Each of these roles related to humanity’s position as ambassadors to the created realm and intermediaries between God and the cosmos. As king, man was meant to rule benevolently, a vassal lord serving at the pleasure of the eternal King.1 St. John Chrysostom writes that God “first erected the whole of this scenery, and then brought forth the one destined to preside over it.”2 So long as man ruled well, he would be entrusted “with complete control over creation.”3 To further reinforce man’s dominion over creation, God brings all the animals to Adam to be named; and they minister to him like servants in a king’s court.4 Yet he was not to become oppressive due to his elevated role; Adam was told to “guard the garden” (Gen 1:15), acting as a wise steward of the world entrusted to his care and avoiding idleness.5

In commanding Adam to “serve and guard the garden” (Gen 2:15), God assigned him a priestly function. These same tasks of serving and guarding were entrusted to the priests assigned to the ministry of the tabernacle and Temple.6 Their daily function was to unite heaven and earth through various sacrifices. But rather than slaying goats and sheep, the first man was called upon to offer up the whole of God’s good creation in thanksgiving. Father Alexander Schmemann writes that, through this priestly vocation, man was called to recognize “that everything in the world and the world itself is a gift of God’s love, a revelation by God of his very self, summoning us in everything to know God, through everything to be in communion with Him, to possess everything as life in Him.”7 St. John Chrysostom writes that if Adam would remain faithful to God, he would gradually, as he was meant to “awaken…to an expression of thanksgiving in consideration of all the kindness he had received [from God].”8 It was not that God needed the praise and offerings of Adam—the Lord Almighty is self-sufficient by nature, and does not need anything man has to offer him.9 Rather, sacrifice is for the sake of man, not for God, so that humans may “learn to win over the supplier of good things, and not to be ungrateful.”10 Offering “thanksgiving to him for [his kindnesses is] . . . the highest form of sacrifice."11

St. John Chrysostom writes that if Adam would remain faithful to God, he would gradually, as he was meant to “awaken…to an expression of thanksgiving in consideration of all the kindness he had received [from God].”8 It was not that God needed the praise and offerings of Adam—the Lord Almighty is self-sufficient by nature, and does not need anything man has to offer him.9 Rather, sacrifice is for the sake of man, not for God, so that humans may “learn to win over the supplier of good things, and not to be ungrateful.”10 Offering “thanksgiving to him for [his kindnesses is] . . . the highest form of sacrifice."11

In addition to man’s royal and priestly duties, he was also called to act as a prophet of God. We often mistake the role of prophecy with that of foretelling the future; but in fact, the Greek term prophētēs (navi in Hebrew) refers to a messenger who receives and announces important news. Only sometimes does the news point to future events that may come to pass. Thus, man was to receive the word of God—the message of his truth, love, mercy, and justice—and to proclaim it to the world. According to Chrysostom, one of Adam’s earliest prophetic acts was to declare “bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh” at the creation of Eve (signifying that Eve is his equal and mate).12 As king, priest and prophet of the universe, Adam is now joined by his queen.

The Fall

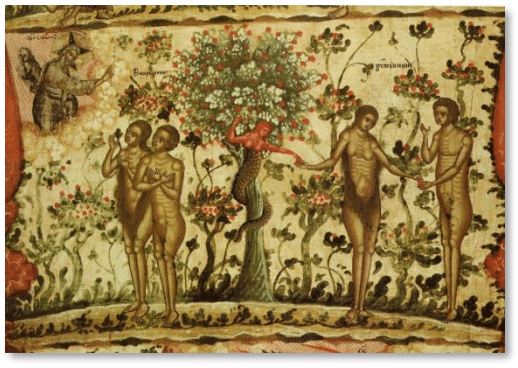

Adam and Eve did not remain in paradise beyond those first idyllic moments. God had placed two trees in the middle of the garden: the “Tree of Life,” and the “Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil.” The first of these was intended to sustain the life of man, and to enable communion with the Living God. But taking and eating from the second tree was forbidden, as God warned it would result in death.13 St. Theophilus of Antioch writes,

God transferred him from the earth, out of which he had been produced, into Paradise, giving him means of advancement, in order that, maturing and becoming perfect, and being even declared a god, he might thus ascend into heaven in possession of immortality. For man had been made a middle nature, neither wholly mortal, nor altogether immortal, but capable of either.14

Yet they grew impatient for God’s gift and prompted by Satan (in the guise of a serpent), they took and ate the fruit of their own accord. By this act of rebellion, they placed themselves in opposition to the merciful God who desired what was best for them. Even so, God imposes death, not as punishment, but as an opportunity: “He set a bound to his [man’s] sin by interposing death and thus causing sin to cease putting an end to it by the dissolution of the flesh, which should take place in the earth so that man, ceasing at length to live to sin, and dying to it, might begin to live to God".15 This event is often referred to as the first or ancestral sin, and sets the stage for humanity’s relationship with God for the rest of history.

The process of man’s temptation described in Genesis 3 is instructive. The serpent initially appeals to Eve’s pride, saying “You will not surely die; for God knows that in the day you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil” (vs. 4–5). However, the narrator tells us that “the woman saw that the tree was good for food, that it was pleasant to the eyes, and a tree desirable to make one wise” (vs. 6), indicating that the initial appeal was to her physical senses and appetite—her eyes and stomach—and only last to her ego. For many of the Church Fathers, the account of the fall teaches us that temptation primarily comes from the world around us (taken in through our senses) and from our bodily desires (welling up from within our flesh). Although we must also confront demonic appeals to our pride, we remain our own worst enemies. And even if we do not sin exactly “according to the likeness of the transgression of Adam” (Rom 5:14), we re-enact the fall in our thoughts, words, and deeds each day.

The primary motivation for Adam’s sin was self-love (philautia), which is a rejection of the selfless love (agapē) that defines the action of God (1 John 4:16). Self-love is called by St. Maximus the Confessor “the mother of all sins”: it begins when we exalt ourselves, and then begins to fester, eventually leading to every other sort of transgression.16 “For since the deceitful devil at the beginning contrived by guile to attack humankind through his self-love, deceiving him through pleasure, he has separated us in our inclinations from God and from one another, and turned us away from rectitude.”17 Selfishness makes it impossible to fulfill the two great commandments:

Jesus said to him, ‘You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, and with all your mind.’ This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like it: ‘You shall love your neighbor as yourself.’ On these two commandments hang all the Law and the Prophets” (Matt 22:37–40).

Acting upon self-love was not only a rejection of God’s command, it also bound Adam and Eve to the physical (sensory) world, plunging them into a matrix of suffering (pathos) where they would continually waver between pain and pleasure.18 Now corrupted, human nature would from then on be plagued by sinful temptations and their own impassioned desires.

The Aftermath

Beginning with man’s expulsion from paradise, we trace a pattern of continual disobedience that marks the remaining narrative of the Scriptures. Time and again, man rejects his calling to be a king, priest, and prophet on behalf of God, and instead brings corruption and death into the world. With this progression into disorder, we find that the three original vocations begin to splinter. Ideally, every family would be wisely guided by the “royal” presence of the father and mother. Likewise, the father would act as the priest for his family (as we see in the case of Job 1:5, where he makes daily offerings for his wife and children), and his wife would assist through her vocation of prayerful intercession. And both were called to proclaim God’s truth, love, mercy, and justice as prophets.

But corruption dissolved this unity of action. Eventually, individuals with specialized roles were chosen by God for certain purposes. Instead of every man acting as a wise king, God would call forth men like David and Solomon to lead the people. Instead of each man making offerings on behalf of his family, God would establish a specific tribe of priests to make sacrifices in a specific location (the tabernacle or Temple). And instead of every person acting as a prophet, God would send designated messengers to Israel to declare his word, men like Elijah and Isaiah. What was common to all three vocations was that each was appointed by God himself, and the sign of this appointment was an anointing with sacred oil (chrisē in Greek – literally “to be christened”).19 By raising up kings, priests, and prophets from among the people and for the people, God slowly prepared the world for the coming of something greater—one who would unite the threefold ministry within himself and truly be the Messiah or Christ (“the anointed one”).

Footnotes

-

“Vassal lord” refers to a political leader who has agreed to a suzerainty arrangement with a more powerful lord and kingdom. The vassal receives protection in exchange for fidelity to the more powerful lord. ↩

-

St. John Chrysostom, Homilies on Genesis 1–17. trans. Robert Charles Hill (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1986), Homily 8.5.

"Why is it, you ask, that if this creature is more important than all these, it is brought forth after them? A good question. Let me draw a comparison with a king on the point of enter- ing a city on a visit: his bodyguard has to be sent on ahead to have the palace in readiness, and thus the king may enter his palace. Well now, in just the same way in this case the Creator, as though on the point of installing some king and ruler over everything on earth, first erected the whole of this scenery, and then brought forth the one destined to preside over it, showing us through the created things themselves what im- portance he gave to this creature." ↩ -

Chrysostom, Homilies on Genesis, 10.11 ↩

-

Chrysostom, Homilies on Genesis, 14.12-19 ↩

-

Chrysostom, Homilies on Genesis, 14.8 ↩

-

We see examples of the priests of the tabernacle/Temple being instructed to “serve and guard” in numerous places, including Numbers 3:7–8, 8:25–26, 18:5–6; 1 Chronicles 23:32; Ezekiel 44:14. ↩

-

Alexander Schmemann, The Eucharist (Crestwood: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2003), 177. ↩

-

Chrysostom, Homilies on Genesis, 13.14. ↩

-

Chrysostom, Homilies on Genesis, 9.12. ↩

-

Chrysostom, Homilies on Genesis, 9.12. ↩

-

Chrysostom, Homilies on Genesis, 9.12. ↩

-

Chrysostom, Homilies on Genesis, 15.12-14 ↩

-

It is important to note that in Genesis 3:6, Eve does not receive the fruit from God, but rather is said to “take” and “eat” it on her own. In the Divine Liturgy at the Anaphora, we quote the words of Jesus Christ, which command us to “take and eat” of his holy Body and Blood in the Eucharist. Whereas Eve stole from God, turning his blessings into a curse, in the Eucharist, God gifts us with his own life in a blessing we freely receive. ↩

-

Theophilus of Antioch, To Autolycus, 2.24 in A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, eds. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace. Vol. 2, Repr., (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1999), 104. ↩

-

Irenaeus of Lyon, Against Heresies, 3.23.6 in A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 457. ↩

-

St. Maximus the Confessor, Four Centuries on Love. 2.8 in The Philokalia: The Complete Text, Vol. 2, compiled by St. Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain and St. Makarios of Corinth. trans. G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherard, and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber and Faber, 1981), 66.8. ↩

-

Maximus the Confessor, trans. Andrew Louth (London: Routledge, 1996), 87. ↩

-

Ad Thalassium 61 in On the Cosmic Mystery of Jesus Christ, trans. Paul Blowers (Crestwood: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2003), 131–2. ↩

-

Some prophets were physically anointed, such as is described in 1 Kings 19:16: “And Jehu the son of Nimshi shall you anoint to be king over Israel: and Elisha the son of Shaphat of Abelmeholah shall you anoint to be prophet in your place.” ↩