Ordained Clergy: Bishops, Presbyters, and Deacons

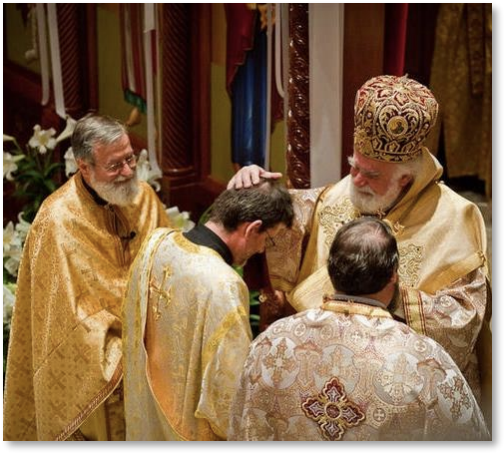

That said, there is a distinction between clergy and laity, in that some gifts are given by the Spirit through the laying on of hands with prayer in the sacrament of ordination. That is because the exercise of some gifts involves authority over the community, and this authority needs to be publicly and widely recognized, acknowledged, and blessed. We glimpse this distinction in Hebrews 13:17, which exhorts the faithful to “obey your leaders and submit to them, for they are keeping watch over your souls as men who will have to give account.”

We also catch other glimpses of this in the New Testament. For example, in Acts 14:23 Luke relates that Paul and Barnabas ordained presbyters for them in every church. The word rendered here “ordained” is the Greek cheirotoneo, which means, “to appoint, choose, install.” The means of appointing presbyters through the prayerful laying on of hands is seen in 1 Timothy 4:14, where Paul reminds Timothy of his own appointment. We see this reflected also in Acts 6:6, with the appointment of men to deal with the church’s financial distribution to the widows (ever afterward identified as the first men to be ordained as deacons): “These they set before the apostles, and they prayed and laid their hands upon them.” A presbyter was one of those who ruled the local congregation with real authority and jurisdiction.

At first, the words presbyter/elder (presbyteros) and bishop (episcopos) were used interchangeably. In Acts 20, St. Paul summons the presbyters of Ephesus (vs. 17) and reminds them that God made them bishops (vs. 28). In his first instructions to Timothy (1 Tim 3), Paul speaks only of bishops and deacons, though he later speaks also of presbyters (for example, in 1 Tim 5:17). In his instructions to Titus, Paul tells him to appoint presbyters (vs. 5) and goes on immediately to describe the worthy candidate as a bishop (vs. 7). These verses indicate that the words presbyteros and episcopos described the same office.

We see this identity of terminology also in such early works as the Didache (c. 100) chapter 15, which encourages the reader to “appoint for yourselves bishops and deacons worthy of the Lord,” with no mention of presbyters, since these were then identical with the bishops.

The same terminology can be found in I Clement (late 1st century). In chapter 42, we likewise read of “bishops and deacons” only. In chapter 44, Clement says that the apostles “knew that there would be strife over the bishop’s office” (literally, “over the name of the bishop”). In the same chapter, he says, “Blessed are those presbyters who had gone on ahead, for they need no longer fear that someone may remove them from their established place.” Thus, we see the terms “bishop” and “presbyter” used interchangeably.

However, just a few years later, in the letters of St. Ignatius of Antioch, we read of the three separate offices of bishop, presbyter, and deacon. Thus, for example, Ignatius writes to the Ephesians, “your council of presbyters is tuned to the bishop as strings to a lyre.”1 Here the offices of bishop and presbyter are clearly distinct. What happened?

writes to the Ephesians, “your council of presbyters is tuned to the bishop as strings to a lyre.”1 Here the offices of bishop and presbyter are clearly distinct. What happened?

I suggest that the development was merely terminological. If the end of the first century saw so profound a change as the creation of a new office, gathering to itself new authority (the so-called “creation of the monepiscopacy”), it is inconceivable that this innovation from the apostolic model would have emerged with no protest or left no record of the ensuing conflict. Yet no record of any such conflict survives. Indeed, Ignatius wrote to the churches of the area, including the Roman church, confident that the same model of governance was in use there, and spoke of “bishops appointed throughout the world.”2 This would be very strange if the three-fold system of bishoppresbyters-deacons was a recent innovation that had not yet spread to other churches such as Rome.

Even during the early days of the first century, one of the bishops/presbyters must have presided at the altar, saying the anaphoral eucharistic prayer. During the first century, this person had (and needed) no specific or unique title. In most communities, he was probably known by his name.3 Soon, when persecution from without and the threat of schism from within made internal unity more important, the role of the presider became necessary, because the people rallied around their leader. The title episcopos was then reserved for him.

But the change of terminology involved no change of structure—the other presbyters continued to rule the church along with their bishop. Thus, Ignatius exhorts the faithful in Magnesia not to do anything “without the bishop and the presbyters;”4 the Trallians were told to “do nothing without the bishop but be subject also to the council of presbyters.”5 There was no change of structure or of power, which is why history records no church protest, for there was nothing to protest about. Presbyters continued to rule under the headship of their bishop, as they had always done.

Footnotes

-

St. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Ephesians, 4:1. ↩

-

St. Ignatius, Ephesians, 3:2 ↩

-

For example, in Jerusalem the presider was known simply as “James”. See Acts 12:17 and Gal 2:12. ↩

-

St. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Magnesians, 7:1. ↩

-

St. Ignatius of Antioch, Letter to the Trallians, 2:2. ↩