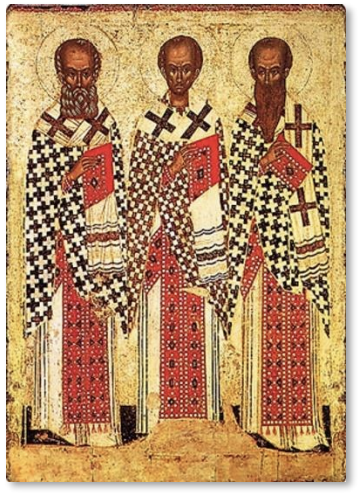

The Place of the Fathers

The question arises, however, “Where can one find this apostolic Tradition in the history of the Church?” The answer: in the consensus of the Church Fathers.1 The Fathers were a varied lot, disagreeing with each other over certain points. They did not all march in lockstep but expressed the sort of variety one might expect to find in men separated from one another by language, time, and geography. For this reason alone, we are not bound by the details of their exegesis of a text, for they differed among themselves in matters of minute exegesis.

But this diversity among them makes their underlying unity shine even more brilliantly, in the same way as the tremendous liturgical diversity of the church at that time made their underlying unity of faith even more impressive. The Fathers are not guaranteed to be authoritative guides, each having some type of hotline to God, verifying the truth of their writings—for how then could we explain their (at times) spirited disagreements? They are authoritative because their underlying core unity witnesses to the apostolic faith diffused throughout the world.

The Fathers share this core unity, sometimes called “the rule of faith,” because they received it from the apostles. In the Creed we confess belief not in “one, holy, catholic, and patristic church,” but in “one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church.” The Fathers are authoritative because their consensus witnesses to the faith they received from the apostles. The Fathers are the conduit for the apostles’ authority, not the source of that authority itself. In their core consensus, we have access to the apostolic Tradition that they received and preserved.

We thus read scripture as part of a worldwide and inter-generational Church community. The individual Christian will therefore read the Scriptures with humility, preferring the time-tested Tradition of the Church to his or her own opinions or supposed discoveries. A modern Christian reader should not approach scripture as an isolated individual, however holy and enlightened they may be. Rather, he or she approaches the Scriptures as one treading a large and well-trodden path, following the exegetical signposts and learning from the insights of all who have gone before. In other words, Christians are called to read the Scriptures on their (metaphorical) knees, and over the (historical) shoulders of the Fathers. As Fr Schmemann wrote, “Any ‘private’ reading of scripture must be rooted in the Church: outside of the mind of the Church it can neither be heard nor truly interpreted.”2

This patristic material is not only available in collections of the Fathers’ writings but is also suffused throughout the liturgical traditions of the Church. The liturgical use that the Church makes of the Scriptures also reflects the mind and conclusions of the Fathers.

That does not mean, however, that new historical tools may not lead to deeper and richer discoveries in the Scriptures. But it does mean that one’s ideas and insights are ultimately offered to the Church to be tested against its collected store of wisdom and the verdicts of others in the community in the time to come. Whether one’s new insights are valuable or not will be proven soon enough. Meanwhile, the modern exegete and theologian will combine both courage and humility in his exegesis, offering insights and submitting to the final ecclesiastical judgment of history.

Footnotes

-

The Church Fathers are the primary spiritual writers, thinkers, and theologians from the post-Apostolic era—classically until the end of the 7th century, but a few extend that range such as St. Gregory Palamas of the 14th c. They wrote about, clarified, and helped to define Orthodox doctrine and the spiritual life. ↩

-

Schmemann, The Eucharist, 79. ↩