The Fall of Humanity

It is an accepted truth that there is something wrong with humanity. War, violence, alienation, abuse, and especially the reality of death, underline for us the basic truth that something is genuinely and deeply off. Some seek for answers in the material order without reference to the invisible world. It is no surprise that they end up empty and vainly seeking after a goal or ethic for creation within evolutionary psychology. Others see that death is the end of all things and either resolve or dissolve into nihilism. And yet others seek to find some kind of meaning for mankind in the structures of society or of mankind. Perhaps ultimate meaning can be had through the pursuit of justice or through humanistic acceptance of the nihil but with a dash of resolve and creativity.

The Christian understanding of this basic incongruity of humanity is summarized in the book of Genesis. There we discover the fundamental problems afflicting humanity according to the Orthodox Church. In short, we have lost our purpose. We exist to commune with God. When we lost our way, all of creation was also bound up in our turn from God. The world itself was subjected to the chaos we introduced into our own souls (Rom 8:19–23). The story of “the fall” in the Adam and Eve narrative is understood by the Orthodox Church differently than in the popular narrative. The alternative way of explaining the fall is that after God created Adam and Eve, he pointed out to them the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and told them to not partake. This arbitrary decision by God was a test for Adam and Eve. Once the sly and deceitful serpent entered the garden, it was simply a test of the desire of Eve to become God—or in other words, her own boss—that prompted Eve to taste the forbidden tree. After this had occurred, it was not hard for Eve to entice Adam. God finds out about the eating of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil and he realizes he cannot abide their sin and has them immediately cast out of paradise to ensure that they cannot partake of the tree of life and live forever. The fall precipitates the wrath of God to also curse Adam and Eve with pain and suffering. The fall of Adam and Eve is basically a prideful breaking of the rules of God and the just consequences due to these acts. The only glimmer of hope is the promise to crush the head of the Serpent.

This common way of explaining the fall has some elements of truth from the Orthodox perspective. However, there is much in this way of telling the story that depicts God and this incident in a rather arbitrary and wooden way. It is arbitrary due to its shallow understanding of God. God appears as a petty and rule-obsessed tyrant. It is wooden in its unlyrical and opaque grasp of the depth of the meaning of the tree, its attraction to Eve, and in the consequences for Adam and Eve in their partaking. Within the Orthodox tradition, the understanding of the depth of the breaking of communion between man and God provides us with a very different picture of God, one more congruent with the rest of Scripture and the God we know as revealed in Jesus Christ.

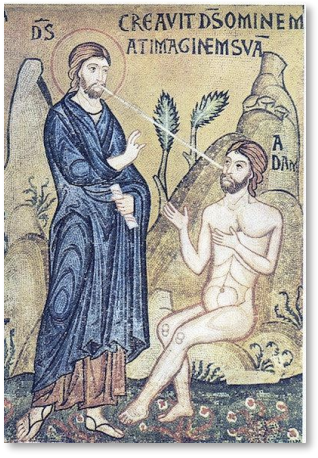

The creation of Adam and Eve is a result of our loving God’s desire for communion. The end of God’s desire to create is to befriend humanity. All of creation is steadily made and declared good by God, but at the end of this work of creation, God declares “Let us make man in Our image, according to Our likeness (Gen 1:26).” Humanity, being made in the image and likeness of God, reflects the special status that humanity has within the cosmos. God further gives to humanity the responsibility and duty of having dominion over the world. Man exists in a special relationship to God - as the sole creature in creation made in his image and likeness and also as the leader and steward of the created order.

Where does God place this unique creation? He places man within a garden in order to tend and keep it. While it may not be obvious to our contemporary eyes, the garden God places Adam within is a garden temple. The orderly account of creation, which ends in the seventh day of rest, underlines for us the building up of the cosmos—not only for man but ultimately as a place for God to rest and rule.1 The garden that Adam is placed in has many parallels to the later tabernacle and the Jerusalem Temple. God walks in Eden as he does in the tabernacle; Eden and later sanctuaries must be entered from the east and are guarded by cherubim; the lampstand (menorah) in the Temple symbolizes the tree of life; the rivers within Eden are later echoed in the prophecy of Ezekiel about life giving waters flowing from a future Temple; and the gold and onyx mentioned in the creation account are used in Temple worship and especially on priestly garments. Adam’s role of stewarding this garden temple is to tend to this garden. The vocabulary used to describe this work are all echoed in the work of the Levites within the Temple sanctuary (Num 3:7–8; 6:26; 18:5–6).2 Adam and Eve’s tending is priestly and liturgical work. Why does God have them do this?

Where does God place this unique creation? He places man within a garden in order to tend and keep it. While it may not be obvious to our contemporary eyes, the garden God places Adam within is a garden temple. The orderly account of creation, which ends in the seventh day of rest, underlines for us the building up of the cosmos—not only for man but ultimately as a place for God to rest and rule.1 The garden that Adam is placed in has many parallels to the later tabernacle and the Jerusalem Temple. God walks in Eden as he does in the tabernacle; Eden and later sanctuaries must be entered from the east and are guarded by cherubim; the lampstand (menorah) in the Temple symbolizes the tree of life; the rivers within Eden are later echoed in the prophecy of Ezekiel about life giving waters flowing from a future Temple; and the gold and onyx mentioned in the creation account are used in Temple worship and especially on priestly garments. Adam’s role of stewarding this garden temple is to tend to this garden. The vocabulary used to describe this work are all echoed in the work of the Levites within the Temple sanctuary (Num 3:7–8; 6:26; 18:5–6).2 Adam and Eve’s tending is priestly and liturgical work. Why does God have them do this?

Adam is the one creature in creation made in the image of God. Man, in the divine image, stands within the garden as the king, priest, and prophet of the world. These three “roles” are not separate and distinct roles that Adam plays but are different ways of explaining Adam’s role within the created order. He is the king, as he is called to govern and steward the world. He serves as God’s representative within creation. He is—as a king—supposed to “concentrate the aims of all existing visible creatures in himself, [so that] he might through himself unite all things with God.”3 For man, being made of spirit and flesh. stands between the boundary between God and the world and mediates and leads all of creation to God.

Because of this role, he also serves as the priest of creation, as he is the one who can “bless and praise God for the world.”4 As chief priest, he is called to “offer a sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving to God on behalf of all those born of earth, thus bringing down upon earth the blessings of heaven.”5 Fr. Alexander Schmemann describes the priestly office of mankind as the ability of man to bless God and thank Him for creation, because man, when rightly following God, is able to “see the world as God sees it and— in this act of gratitude and adoration—to know, name and possess the world.”6 Man is, in his very nature, a priest. Schmemann further elucidates,

[Man] stands in the center of the world and unifies it in his act of blessing God, of both receiving the world from God and offering it to God - and by filling the world with this eucharist, he transforms his life, the one that he receives from the world, into life in God, into communion with Him. The world was created as the “matter,” the material of one allembracing eucharist, and man was created as the priest of this cosmic sacrament.7

Adam also is created to be a prophet. He is ordained to proclaim “the will of God in the world in word and deed.”8 Adam sits and directs creation as king. But having truly seen creation and directed accurate praise to the Creator, he serves as priest. It is as prophet that Adam names the creatures and proclaims the true reality of creation to creatures. To accurately direct, give thanks, and to proclaim the truth of reality—that is the work of Adam. With these sketches of man’s role within creation, we can now more adequately account for what went wrong in the garden of Eden.

Read more: Pre-History (opens in a new tab), Sin (opens in a new tab), Man (opens in a new tab), Priesthood (opens in a new tab)

Footnotes

-

T. Desmond Alexander, From Paradise to the Promised Land (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2012) 119–133. The theme of gods active in building creation as a temple for them to reside and reign in is a central theme in Mesopotamian mythology. ↩

-

Alexander, From Paradise to Promised Land, 124. ↩

-

Metropolitan Macarius as found in, Michael Pomazansky, Orthodox Dogmatic Theology (Platina, CA: St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2009), 141. ↩

-

Kallistos Ware, The Orthodox Way (Yonkers, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1995), 68. ↩

-

Pomazansky, Orthodox Dogmatic Theology, 141. ↩

-

Alexander Schmemann, For the Life of the World (Yonkers, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1997), 15. ↩

-

Schmemann, For the Life of the World, 15. ↩

-

Pomazansky, Orthodox Dogmatic Theology, 141. ↩